On voices from the wilderness: “where we go from here…”

We recently lost two very important Kagyu Rinpoches, Karma Chagme, the head of the Nyedo Kagyu and direct lineal descendent of the great mahasiddha Rāga Asya , the very emanation of Amitabha himself, and Kyabje Choje Akong Rinpoche, a great social activist, dharma teacher. Along side Trungpa Rinpoche, Akong Rinpoche as one of the most important Kagyu Rinpoches in how he helped to plant the seeds of dharma in the West, but also create nurture Samye Ling and the system of Samye Dzongs throughout the UK, Scotland, Ireland, Europe and Africa. He was also vital in helping to local the young 17th Karmapa. As a lineage we have also recently lost Kyabje Traleg Rinpoche, Kyabje Tenga Rinpoche, and still feel the loss of Kyabje Bokar Rinpoche.

As long as His Holiness the Gyalwang Karmapa is with us, no matter where he resides, I feel that we are in good hands, and as a student of His Eminence Goshir Gyaltsab Rinpoche, I feel that as long as his activities continue then the dharma will not only flourish but increase in concentration and power. May their lives be long and may they completely destroy our ego-clinging through the power of their skillful means! May their activities increase the depth and wisdom of the Kagyu lineage!

This said, there are some who express concern about where we as Karma Kagyu are going in the West, and I would like to throw my two cents into the ethereal debate. Rather than make this a global argument, metaphorically as well as actually, maybe we should just focus on the Kagyu in America. I do not presume to know much at all about this subject, and even more than that, I have no real qualifications to weigh-in on such a topic, but nevertheless, as one who has deep love for our lineage I am occasionally concerned about how we may be structuring ourselves here in the U.S.

As Karma Kagyu I feel that we can do more than we are doing. We obviously benefit from the hard work and extreme diligence and patience of the masters of the early era: the late Kalu Rinpoche, the late Trungpa Rinpoche, ven. Khenpo Karthar Rinpoche, Thrangu Rinpoche, Bardor Tulku, Ponlop Rinpoche, Lama Norlha, Lama Lordro, Lama Tsingtsang, Lama Rinchen, Lama Dorje, and of course, their guide His Holiness the Gyalwang 16th Karmapa, Rangjung Rikpe Dorje. We owe them a debt of gratitude. Through these teachers we have the benefit of some very solid infrastructures for the study and practice of the dharma- we have a great number of translators, translation committees, places for extended as well as short retreat as well as the beginning of a sangha which while still young and tender might hopefully grow into a single unified family of victorious ones. Yet right now the sangha may be our weakest link.

America is a unique place in that across the board we like to think of ourselves on the collective level as a unified group that share similar values, and yet we also very easily cleave along a variety of lines that include ethnicity, religion, gender, sexual orientation, race and political views. The obvious benefit is that there is the potential for most anyone to find a niche within the American experience. The fundamental flaw is that we are only part of the group until we don’t want to be, until our desire-lines of identity pull us into our sub-groups. When we separate from the collective in this way, the American experience becomes very static and disjointed. Likewise, when we try to singularly drop our histories, the various layers of culture that have helped to shape us as people, in favor of the collective identity, we lose the richness and the brilliance that we bring to the entire American organism. There is something about the fundamental tension between the more idealized identity as Americans (which is a construction) and our identity as a member of a variety of sub-groups (also ultimately a construction) that allows us to question the values of both sides of our being that can allow us to grow into dynamic citizens. That said, there is nothing preventing us from remaining stagnant within our identity on either side, either a stalwart “American” or member of a sub-group that doesn’t want to be part of the collective . When this happens unity, connection and communication becomes impossible.

Similarly, the essential flaw that we as American Karma Kagyu face is the idea that we actually think that know what we are doing. We feel that we are correct in projecting a particular meta-view upon ourselves as followers of the wisdom lineage of the Karma Kagyu, and that this view has to be expressed in a particular unified way. We assume that we must all adhere to the values as a group that were most recently innovated by Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Thaye in 18th century Tibet, who while being an amazing genius and autodidact, has been used (perhaps unintentionally) to create a blanket meta-identity that may have been taken to the extreme. At times I feel that ultimately this lack of balance has led many who feel connected to a wide variety of sub-groups to feel left out and as a result, not integrated into the larger view of what we may be as a lineage. As if the notion of a unified Karma Kagyu lineage, or any lineage, has ever existed until the “modern” era.

I think that it is worth throwing into the mix that the lines of all four major schools of Tantric Buddhism might be more a product of modern academia than anything else. It might even be that we have all contaminated one another through the cross-pollination of inter-lineage growth in the past than our projections and assumptions allow us to believe. Our identities are more blended that we might like. An example of this can be demonstrated by His Holiness Sakya Trizin when he recently gave the empowerment of Dudjom Lingpa’s Three Wrathful Ones in New York City.

I think that it was Trungpa Rinpoche who called the Kagyu lineage the ‘mishap lineage’, which I will loosely interpret to mean that at its best our lineage just happens; it is not the product of strategic planning. Why is this? Well, perhaps we are not the product of controlled strategic planning either; our mind/heart matrix of thought/emotion is a system of constant mishaps, all sorts of stuff arises, sometimes we can clearly rest in what arises, other times we get carried away by our hallucinations. But one thing is certain, problems arise once we try to force a structure upon the way things should be.

In this way, I tend to wonder if we may have made the fundamental error of leaning too much upon the 18th/19th century classicism of monastic Karma Kagyu as a model for the entirety of American Karma Kagyu (the vast majority of whom are lay) in the 21st century. It sounds kind of absurd actually when I see it written out like that, and I don’t think that it is too much of a stretch to suggest that if this is the case, then perhaps we lose some of our credibility and accessibility with those who resonate with the sub-groups that feel at odds with the way the dharma is presented. How are young people with little interest in India or Tibet, let alone their history, and who have little money to travel to India to feel connected? What about some curious souls from the South Bronx, Brownsville, Oakland, Compton, or even large swathes of Suburbia who want to better understand their relationship to their experience of suffering to connect?

The dynamic energy of engaged being as is inherently expressed by a wide variety of groups of all imaginable ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, race and other points of orientation doesn’t seem to be held by the container of this kind of singular classical Tibetan approach. Perhaps it is paternalism or some type of chauvinism, and perhaps it isn’t- lord knows the internet is full of such debates, and my point here is not to cast blame upon anyone other than our limited view. That said, I tend to feel that what matters most here is that the essential tension between “self-identity” as a member of any particular group in relation to the experience of gaining certainty in our not having any particular “self” as taught through the dharma is being lost to an increasing number of Americans. These sparks of tension allow the power of tantric Buddhism to blow up our ideas of who we think we are and how we tend to conceive of the world around and within ourselves. To ‘inadvertently’ create the assumption that one can only experience this through assuming that we all need to be conversant in 18th/19th century Tibetan classical Buddhist thought only serves to disempower the vast majority of sentient beings in the United States. It allows few people to come and be held as they expolre the sparky nature of what it means to familiarize oneself with the view. Perhaps Europe is different, or Central and South America, and Aftrica, but I suspect not.

The way that much of the Karma Kagyu lineage is being presented these days in the United States appears to be more of a preservation of monasticism and the imposition of this structure upon the inner lives of the sangha, rather than a skilled blending, meeting people where the are, and creating the container that allows the safety and intimacy necessary to challenging the assumptions of who and what we are, and what the whole field of appearance might be.

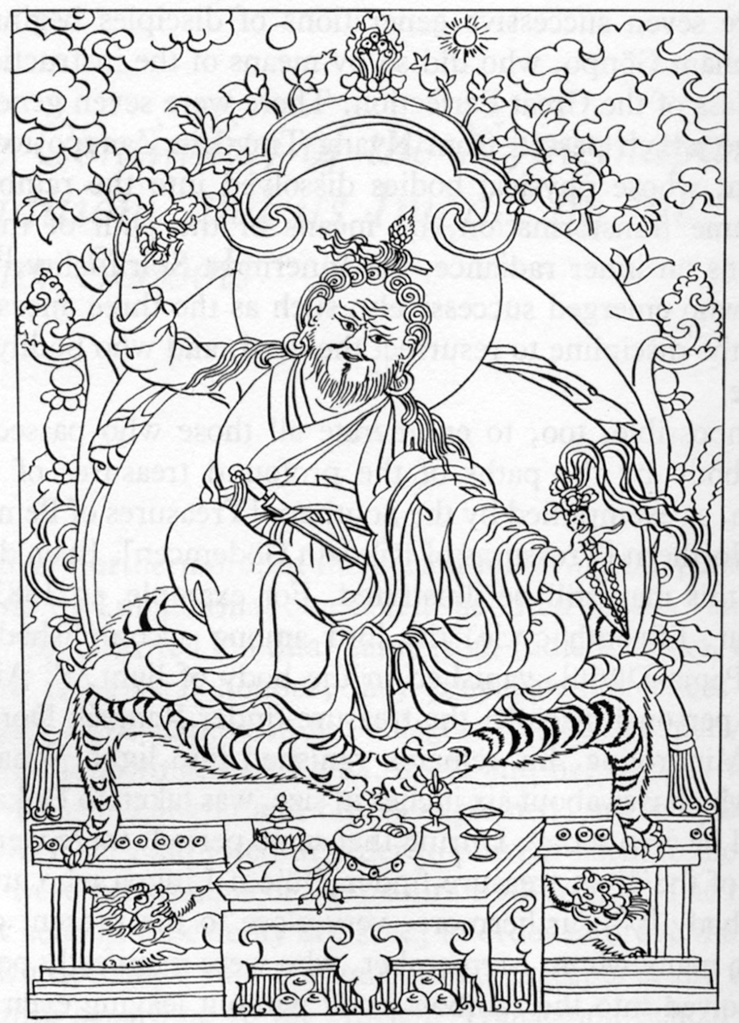

The result is that it is not uncommon to find that there are many gorgeous Karma Kagyu dharma dharma centers, stunning in beauty and immaculate in appearance, real museum quality reproductions of what one might have found in Tibet before the Chinese holocaust. Yet, it is also possible to feel the cold clinical nature of many of these places. In looking even closer, it is easy to see how tender and fragmented the sanghas appear. This makes me feel sad. After all, it is sangha that is vital for the continuation of the practice of dharma. When I visit places that resemble these perfect visions of what dharma is supposed to look like visually, I think of Drukpa Kunley, Milarepa, Phadampa Sangye and Shabkar with great tenderness (and humor) and take delight in my meager identity as a so-called Repa. These teachers (myself completely excluded) were vital commentators, alternatives and voices in the wilderness that dharma cannot be owned, trapped in books, and is not only to be delivered through the medium of classicism which often runs the risk of becoming overly dusty and theoretical. There is a lot of wisdom in their path, and many teachings in their relationship with the institutions that presented dharma in a particular kind of way.

What we seem to fail to realize, or perhaps disassociate from, is that the Karma Kagyu lineage is best when it is a blended practice of fierce engaged practice activity mixed with the subtlety and discipline that one finds in Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Thaye. Just as we need the sun and the moon for there to be balance on Earth, perhaps we need both the paths of Rechungpa and Gampopa as symbols of who we are, who we might wish to become, and from which point we wish to engage the dharma. We need to look at where we become too comfortable and lazy and bring our whole experience as people into our practice. Good dharma practice has nothing to do with beautiful dharma centers, rich coffers, and exquisite elegance. In fact, the best practice arises from confronting the entire hallucination of this “self” and the world around us. We are often well served to this end in challenging our assumptions of how our dharma centers should appear, notice when our devotion becomes the habit obsession rather than a mixture of connection and gratitude, and when in trying to be “good”, how we accidentally cause great harm to those we tell ourselves we are committed to benefiting.

Ultimately, everything that has been created by our foreparents within the Karma Kagyu in America is wonderful, and we should rejoice in the amazing progress. It really is amazing what has come into being. And yet, we might be getting a bit lazy and myopic and I pray that we can make things a bit more messy and sparky and dynamic for everyone who might be attracted to this vibrant and wonderful lineage. I pray that our dharma teachers can strike a rich and engaged balance for their students! I pray that our lineage can hold the experience of every person from every walk of life who approaches us! I pray that we face mishaps every day and that the sparks of tension within our experience of being cause endless dakas and dakinis to bless us!

On resting with Tilopa…

Recently I have found myself returning to some of the amazingly pithy meditation instructions attributed to Sri Tilopa (988-1069), the well-known Indian Buddhist mahasiddha who was the forefather of the Kagyu lineage. His short, often poetic instructions, are something that help me in my personal meditation practice, as a ground for keeping myself feeling dynamic and internally connected as a chaplain, and in explaining to others the vajrayana perspective regarding what arises within the approach to death. An example of such an instruction is as follows:

If you sit, sit in the middle of the sky.

If you sleep, sleep on the point of a spear.

If you look, look upon the center of the sun.

I Tilopa, who saw the ultimate, am the one who is free of all effort.

The expansive clarity of this type of instruction, for me at least, is very resonant- it offers a way to feel my experience of mind blend into the wideness of space while also experiencing a sense of focus; a relaxed single-pointed experience of breath, sound, transparency of thoughts, and edgelessness. When this experience arises I feel very connected with Tilopa, as well as the other Indian mahasiddhas Naropa and Maitrepa. Sometimes however, I feel that I need a more graded approach to this experience of mind. When this occurs, I tend to lean on Jey Gampopa for support.

More specifically, I rely upon Gey Gampopa’s Precious Garland of the Supreme Path, and even more specifically I come back to the 5th chapter of this wonderful text: The ten things that you should not abandon. I had the wonderful fortune of receiving instruction on this text by the Venerable Khenpo Lodro Donyo, abbot of Bokar Ngedhon Chokhor Ling, in Bodh Gaya in the fall of 1998. This was during one of the many Mahamudra seminars that the late Kyabje Bokar Rinpoche held- truly magical times when we could all sit together under the bodhi tree to recite the 3rd Karmapa’s Mahamudra Aspiration Prayer, spend time in meditation- simultaneously touching our original nature- as well as physically touching the ground that supported the practice of all of the generations of Buddhists who had come before us in Bodh Gaya back all the way to Shakyamuni himself.

It was in that environment, and within that emotional frame of mind, that I came to learn of the ten things that one should not abandon. These ten things are: compassion, appearances, thought, mental afflictions, desirable objects, sickness (suffering and pain), enemies or those who obstruct our practice, methodical step-by-step progress, dharma practices involving physical movement, and the intention to benefit others. Gampopa’s list is very sensible, it is noble in the sense that it seems to be endorsed by Santideva himself; it is imbued with a heartfelt concern for the welfare of others as well as a methodical presentation of the training to see that appearances- be they attractive or not- are just mere appearance. The misapprehension of appearance, or appearance as taken as an independent entity separate from ourselves, is the very cause of our experience of suffering. As with all great dharma texts, it is heartening to see how just one small portion, in this case the 5th chapter of a 28 chapter text can offer the entire path to realizing one’s essential nature.

In looking back at the notebook that I have from the session when Khenpo Rinpoche taught this chapter, I can return to my exuberance not only for this chapter as a whole, but for Gampopa’s explanation of how one should approach the non-abandonment of mental afflictions. As a chaplain, when I am in the hospital, I very rarely meet people who desire to not abandon their experience of suffering: their fear, their psychic pain, their feelings of abandonment, of futility, of anger, or attachment to family- let alone attachment to ideas of how their life should or shouldn’t unfold. This experience isn’t unique to the hospital either- I and most of the people who I know spend a great deal of time fighting with these emotions. Perhaps this is why they are called mental afflictions.

Anger, attachment, pride, jealousy, ignorance. When we really sit quietly with these words they are not just words- they are worlds; worlds of suffering, worlds of feeling like we are right and others are wrong, that we don’t receive the credit or accolades that we deserve, that if only I had this, or was a that, then things would be the way that they should be. On and on and on…

Gampopa advises us to try three modalities with regard to facing and not abandoning our mental afflictions. We can avoid them- that is, avoid whatever causal conditions that might make them arise. We can transform them- or try to transform what these emotions unlock within us. Or finally, we can rest in them as they arise. Whichever modality we tend towards, there are two things to remain mindful of; how we habitually fall into one of these three modalities, and the degree to which we can honestly assess our relationship to that which we struggle with. Each of these ways of facing and not abandoning our mental afflictions can be techniques of liberation or techniques of seductive self-enslavement.

The process of avoidance is a very grounded, stable and well-meaning way of not abandoning our mental afflictions. It honors the way they arise- it honors their root- without forcing us to become affected. This way of approaching difficulties, painful habits, and stubborn aspects of our identities allows us some distance from the “heat” of the moment that comes with embodying our reaction to our mental afflictions. One could even go so far as to say that this modality is somewhat analytical in approach, it is disciplined and measured. The shadow aspect of avoidance is not acknowledging the mental afflictions that bring us pain and suffering. Not much good happens from simply ignoring things, or not letting aspects of ourselves have the light and air that they need to grow. Right now, the shadow of this modality comes to mind in the form of the image of a neglectful parent who doesn’t want to see who their children really are.

Transformation is a common methodology that one finds in the various levels of tantras. It involves playing with the way that we perceive our mental afflictions. This type of restated relationship allows us to meet head on those feelings that would normally make us want to run away. In this way the dross becomes pure; the dirty is seen as clean; and that which torments us achieves the possibility of bringing meaning and peace. True lighthearted transformation- transformation with ease- is hard to effect. Transformation has a terrible shadow side that involves the desire to fix; or more bluntly an inability to meet things as they appear without making them into something positive. As a chaplain, I witness many people struggle with maintaining a relationship with difficulty and pain, uncertainty and loss, and sickness and death without trying to “fix it”. The constancy of a “make-it-better-plan” can be exhausting and create untold suffering. It feels profoundly important to examine how this modality of maintaining a relationship with our matrix of painful emotions can relate to a desire to not allow honesty around what we are feeling and from where the roots of these emotions arise. (Here is a link to the related shadow of spiritually bypassing.)

Resting in whatever arises, the third modality presented by Gampopa, and the favorite of Khenpo Lodro Donyo while he was teaching, is an instruction that one commonly finds within the Kagyu and Nyingma traditions. It is profound- and it also very difficult to do honestly. As we saw earlier, anger, attachment, pride, jealousy and ignorance are powerful. To rest within rage for example- to feel one’s pulse quicken, and heart beat heavier and louder, while one becomes physically tight and flushed, as the explosive heat of anger and impatience engulfs us- is not a particularly comfortable feeling. (For a look at some of the difficulties involved with taking on these fierce emotions, you can read a previous post on Mahakala here.) Then there is the “resting” part. This term gets thrown around very often that I wonder if it doesn’t end up having a multitude of meanings nowadays. I know that I have met Buddhists of other traditions that take the term literally and assume that it is akin to taking a nap or “resting”.

Resting actually refers to maintaining a focused (often described as ‘single-pointed’) awareness of appearance as it arises in the moment. In this way, Tilopa’s instruction from the beginning of this post seems a wonderful way through which we can re-engage the term resting. One quality of resting is being at ease. In this sense when Tilopa refers to three different ways of being- siting, sleeping, and looking- he is referring to three ways that we can rest in what arises. We can do it formally, as in sitting practice. We can do it within the experience of sleep, mind appearances arise when we sleep just as when we are awake. Finally, in looking, perhaps a passive “every day” experience as well.

If you sit, sit in the middle of the sky.

Where is the middle of the sky? The true middle? Where are its edges? Where does the sky end and something else take over? As we sit and remain resting with a sense of ease can we feel the expansive qualities of our minds? Where is the edge of our mind? What does a thought look like? Does it have a source that you can identify? Where do thoughts go when they are no longer so magnetic?

If you sleep, sleep on the point of a spear.

When our thoughts feel sticky and magnetic, when it is hard to not feel drawn into them and let our inner film projector play, what happens when we remain concentrated? What does that “single-pointed” awareness feel like? When we can feel and notice our breath; when we can maintain focused awareness on the way the inner film projector plays; on how a particular thought will hold us within our inner gaze, what do we notice about our experience?

If you look, look upon the center of the sun.

When this focus can be maintained as we look out at the world as it goes by around us, where is the sense of stillness? From where does that arise? What happens to the way that you notice the way that things arise while maintaining a focused awareness upon the expansive quality of our minds? Is there ever not enough room for what arises within our field of reference?

I Tilopa, who saw the ultimate, am the one who is free of all effort.

What if removing all effort was all that you had to do? What would it be like to maintain that within your experience of life?

Instructions such as the ones that Tilopa left behind for us are rare and powerful. It has been roughly one thousand years since Tilopa passed away, and yet through these four lines it is amazing how much of a connection we can feel with him. Five generations after Tilopa, Gampopa further crystalized the importance of being someone who “is free of all effort”. And while there are may pitfalls around how we may feel that we are directly engaging what arises within the moment, there is much beauty in the journey. Perhaps, slowly moving through life, through the wonderous field of appearance, we can increase our sense of ease and relax into an experience of effortlessness. What an amazing thing to aspire towards.

on how we can be close to the karmapa: what it means to be kagyu

The recent events surrounding His Holiness Orgyen Trinley Dorje have been extremely painful to watch. I realize that I am not the only person who has strong feelings about the present situation. Right now it feels important to bring these feelings inward and let those who are much more skillful and experienced with the complexities of these issues remain at the forefront. Perhaps directing all of the emotions that arise from the present situation towards practice, and using this present moment to reflect upon the Kagyu lineage can be a powerful tool for connection and empowerment. Rather than add to the frenzy of internet activity through discussing what has been going on, I would like to respectfully let the Office of His Holiness the 17th Gyalwang Karmapa with its advisors lead the way, they are wise, capable and have my complete confidence.

So let’s go deeper. What does it mean to be Kagyupa?

Practice. Devotion. These qualities are certainly not solely owned by the Kagyu lineage, or even vajrayana buddhism for that matter, but they are the special signature of this precious ear-whispered lineage.

What does that mean?

The relationship that the great Pandit Naropa had with his radical, skillful and essential guru Tilopa was one of great intimacy and tenderness. It was a relationship of sharing, where a master tested and took great care in exhausting the neuroses and misapprehensions of his student, who through his own dedication and drive, applied the special instructions and worked hard to guard and tend to the experience of enlightenment. Master and student lived side by side so that any ordinary experience could be used as a tool for revealing the dharma. In creating the a relationship of close intimacy Tilopa challenged Naropa, he knew what buttons to push, he chided Naropa’s intellectualism, and ultimately empowered him to experience buddhahood.

Marpa the indomitable angry Tibetan farmer- stuborn and hard-headed- decided to leave Drogmi Lotsawa to find and experience dharma on his own, for himself. Undergoing a series of journeys through out Nepal and India he eventually found his guru, Naropa. Marpa had to bear the brunt of being Tibetan in 11th century India, not an easy task Tibetans were generally regarded as rough and not that intelligent by their Nepali and Indian contemporaries. Indeed, the mahasiddha Sri Santibhadra (aka Kukkuripa) to whom Marpa was directed to initially receive the transmission of the Mahamaya Tantra asked why he should give the empowerment of the Mahamaya Tantra and subsequent explanations to a “stupid flat nosed Tibetan?” That must have really pushed the buttons of this precocious, driven seeker who was known for having a short fuse! The relationship between Naro and Marpa, like that of Tilopa and Naropa, was also intimate and close- Marpa spent years actualizing the paths that were offered to him from his primary guru, Naropa. Marpa also maintained close relationships with the mahasiddhas Maitripa, Kukkuripa, as well as Saraha (in the dream-state). Marpa brought the instructions of these great masters back to Tibet and firmly placed the victory banner of the kagyu ear-whispered lineage upon the Tibetan Plateau.

Milarepa, the repentant magician suffered great loss early on in his life. Imagine the loss of everything you know as one of your parents die, imagine that all you have every owned, or all that has ever been promised to you has been taken by family that you trusted. Imagine the shame and guilt, the remorse and regret that Milarepa must have felt growing up- imagine those feelings distilling into the deep focus to harm others. Marpa, the farmer lama, with his liberating presence, took the time to be there for Milarepa as a teacher in the best way possible. He had the skill to know that forcing Milarepa to perform nearly impossible tasks of physical labor to ripen his karma, to help push the reset button, and to reveal wholeness where previously there was just suffering, was appropriate. After all, Milarepa had been to a teacher before Marpa who was much looser in his teaching style which didn’t fit with Milarepa’s attitude. As a result not much occurred between Milarepa and this other teacher. Marpa, ever the farmer, planted the seeds of dharma within Mila’s being and carefully, tenderly raked, weeded and fed these seeds until the grew into a rich crop.

Rechungpa and Gampopa, the left and right hands of Mila Laughing Vajra, expressed the wisdom, instruction and blessings of their father-like lama. Gampopa did this through codifying and merging the ear-whispered lineage of experience with his experience as a Kadampa monk thus providing a monastic base for the Kagyu lineage; his famous Jewel Ornament of Liberation is a classic lamrim (stages of the path) presentation of the dharma. Rechungpa, a repa or cotten-clad yogi, continued more within the activity tradition of Marpa Lotsawa, returning to India to procure the empowerments and instruction for the practice of the Formless Dakini, a lineage that is still maintained within the Drikung Kagyu lineage. Both Rechungpa and Jey Gampopa were cared for by Milarepa- they had very close and different relationships with Milarepa. The devotion and sadness that Rechungpa expressed upon learning of Milarepa’s death is a beautiful reminder of the internal connection that they had. It also feels important to note that the last thing that Milarepa shared with Gampopa was showing him his calloused buttocks- a final testament that practice is essential, that the experience of liberation is supported by practice.

The Kagyu lineage, and all of its branches, is often refered to as a practice lineage. And indeed, if one took a look at the lives of the lineage holders, one can see that great care has always been applied to the maintainance of the purity of the lineage, as well as experiencing or tasting its essential essence. When we look at the lineage of the Karmapas, Tai Situpas, the Gyaltsabpas, the lineage of Jamgon Kongtrul Rinpoche, Traleg Rinpoche, Thrangu Rinpoche, Tenga Rinpoche, Sangye Nyepa Rinpoche, Trungpa Rinpoche, Kalu Rinpoche, Bokar Rinpoche, Mingyur Rinpoche, Chokgyur Lingpa, Karma Chagme Rinpoche, Khamtrul Rinpoche, and many other great Rinpoches, and unknown practitioners, it is amazing how alive and energetic the Kagyu lineage is.

I sometimes feel that people believe that being Buddhist involves shunning the world and keeping ourself calm and without emotion. In the hospital I am often asked by patients how I have the strength to not feel or to remove myself from the world. I don’t have that strength, I’m not even sure if that is a strength, and even if I did, I wouldn’t want to remove myself from the world. There are worlds upon worlds within us, physical isolation or separateness alone doesn’t change that. The freedom we seek is found in embracing what is right infront of us. Buddhism is in the midst of being translated to the western idiom. It has firmly taken root in many respects, however I feel that a significant point of focus may need to be how we as Buddhists (perhaps more so for vajrayana Buddhists, although maybe not) can maintain sacred-outlook as well as a realistic understanding of the world around ourselves. How can we connect to the visionary nature of our lineages, create real connection, feel that we are part of them, recieve the blessings of their transmission history without having an overly utopian notion of how everything constellates with the world that we live in?

A few years ago I read a translation of a text by Raga Asay, the first Karma Chagme Rinpoche in which a story was related about Raga Asay who after recieving instruction from the 10th Karmapa Choying Dorje, prefered to live far away from Tsurphu. When asked by a friend why he would choose to live far away and not be able to attend public events (empowerments, reading transmissions, teachings, etc.) Raga Asay replied,” when I am in retreat the lama on the top of his head is near and I always feel his blessings. When I am at Tsurphu my mind is plagued by insecurity, jealousy and gossip.” Karma Chagme found the balance; his balance, a confidence in his relationship with His Holiness as well as with the larger lineage. At the same time Karma Chagme seems to be suggesting “people are people are people”- we gossip, brag, and in all our enthusiasm during special religious functions often inadvertantly act unskillfully.

In terms of the present situation, it is easy to pick up on and focus on the politics, the gossip, and the intrigue and forget that this is all appearance. By all means we should support His Holiness, but as his children perhaps we should bring what arises within us to the path. This is what Gampopa refers to when he lists the ways to deal with obstacles to practice, we can try to abandon obstacles, or we can transform them, or we can rest within them as they arise. Gampopa suggests that transforming obstacles is good, but that resting in them may be better- it is a way to bring direct experience of the present moment to our practice. In facing our fears, our insecurities, our rage, our frustration, and being able to be aware of this as none other than the play of our mind, we are able to be clear and free.

When His Holiness came to Mirik to consecrate and install the kudung stupa of Kyabje Bokar Rinpoche, His Holiness told the large group of Kyabje Bokar Rinpoche’s students that our greatest offering to Bokar Rinpoche is our practice. That to put into practice his instructions, and to aspire to completely master master them, we are connecting in a profound manner to Kaybje Bokar Rinpoche. This sounds like timely advice for the present moment, but also something to keep in mind at all moments. While we can not always serve our lama in an everyday setting, we can serve our lama by holding dear and practicing the instructions that she or he offers us.

The office of His Holiness recently offered a statement of thanks to everyone who has supported His Holiness and his labrang and suggested that we offer our practice towards the removal of all obstacles towards the problems that His Holiness has faced. You can read it here. This is wonderful! I cannot think of a better way to maintain a connection with such an amazing teacher. In practicing for him, we are generously offering our time, our effort, our spirituality as well as our connection with the lineage from which the instructions that we follow flowed from. This is an offering beyond time and space; an essence offering which when fused with the intention of benefiting His Holiness and his labrang- doubtless, this is a powerful way of maintaining connection, it’s a way through which we can feel the heartbeat of Tilo, Naro, Marpa, Mila within our very being.

Although all practitioners have a lineage,

If one has the Dakini lineage, one has everything.

Although all practitioners have a grandfather,

If one has Tilo, one has everything.

Although practitioners have a lama,

If one has Naro, one has everything.

Although practitioners have teachings,

If one has the hearing lineage, one has everything.

All attain the Buddha through meditation,

But if one attains Buddhahood without meditation,

There is definite enlightenment.

There is no amazing achievement without practice,

But there is amazing achievement without practice.

By searching, all will find enlightenment,

But to find without searching is the greatest find.

-Marpa

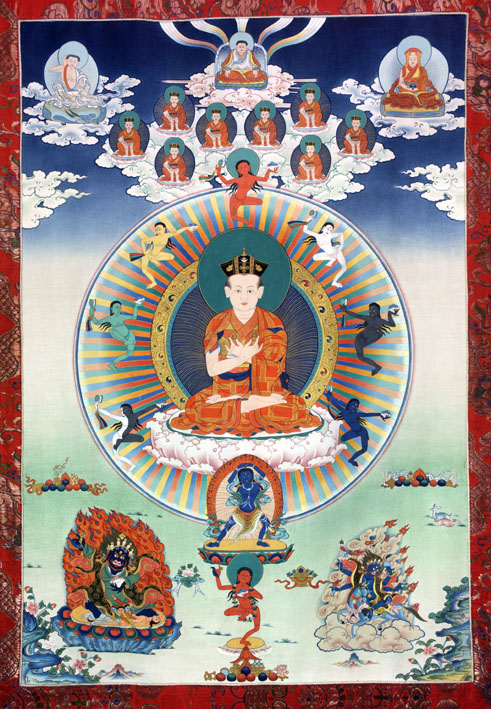

Kalu Rinpoche and Bokar Rinpoche, Father and Son, protectors of the Kagyu Monlam.

It has always felt to me that if Kyabje Kalu Rinpoche was the essence of Milarepa, then Kaybje Bokar Rinpoche was the essence of Gampopa. While I never had the chance to meet Kalu Rinpoche, I have met many Tibetan, American, British and French students of Rinpoche who often spoke of his direct orientation towards practice, his passion for transmitting instruction, and his easy going trust in the dharma- these seem to be qualities that I associate with Milarepa.

Similarly, Bokar Rinpoche with his purity of heart, emphasis upon transmission of the lineage teachings and stainless vinaya, truly does remind me of qualities that were emblematic of Je Gampopa. In expressing the direct simplicity of mind, Kyabje Bokar Rinpoche was known as a great master of Mahamudra.

That they both maintained, preserved and expanded the Kagyu Monlam in Bodh Gaya is important. Kyabje Kalu Rinpoche can be credited with establishing the Kagyu monlam in Bodh Gaya. When he began the monlam it was a small informal gathering. After his passing, Kyabje Bokar Rinpoche continued the practice of maintaining and further developing the Kagyu monlam; it slowly grew and grew. I attended several of these earlier monlams where Bokar Rinpoche and Yangsi Kalu Rinpoche presided over a much smaller number of monks, nuns and lamas than those that attend present monlam celebrations. They were a combination of grand and intimate, which seemed just right for reciting aspiration prayers and receiving inspiration.

After His Holiness the 17th Karmapa escaped from Tibet in January of 2000 and was allowed to travel inside of India, he presided over the monlam. Its as if Kyabje Kalu Rinpoche and Kyabje Bokar Rinpoche were keeping his Holiness’ seat warm under the bodhi tree. Since the sudden death of Kyabje Bokar Rinpoche, the monlam has been run by Lama Chodrak (the lama he appointed to organize the monlam) and the monlam committee. His Holiness the 17th Karmapa has also taken a strong role in monlam planing, and feels strongly about its mission and goals.

With their activities in mind I offer this song of supplication written by Kaybje Bokar Rinpoche. May it be of benefit!!

Wide Wings That Lift Us to Devotion: A supplication

A Vajra song by Kyabje Bokar Rinpoche

Spiritual master, think of me! Think of me!

Source of all blessings, root spiritual master, think of me!

Spiritual Master, think of me! Think of me!

Epitome of all accomplishment, root spiritual master, think of me!

Spiritual master, think of me! Think of me!

Agent of all enlightened activity, root spiritual master, think of me!

Spiritual master, think of me! Think of me!

All refuges in one, root spiritual master, think of me!

Turn all beings’ minds, with mine, towards the Teachings.

Bless me that all stages of the faultless path-

Renunciation, the mind of awakening, and the correct view-

Genuinely arise in my being.

May I dwell untouched by the faults of pride and wrong views

Toward the Teachings and the teacher of freedom’s sublime path.

May steadfast faith, devotion and pure vision

Lead me to fully achieve the two goals for others and myself.

The Human tantric master introduces my intrinsic essence.

The master in the Joyful Buddha’s Canon instills certainty.

The symbolic master in appearances enriches experience.

The ultimate master, the nature of reality, sparks realization of the abiding nature.

Finally, within the state of the master inseparable from my own mind,

All phenomena of existence and transcendence dissolve into the nature of reality’s expanse;

The one who affirmed, denied and clung to things as real vanishes into the absolute expanse-

May I then fully realize the effortless body of ultimate enlightenment!

In all my lifetimes, may I never be separate from the true spiritual master.

May I enjoy the Teachings’ glorious wealth,

Completely achieve the paths and stages’ noble qualities,

And swiftly reach the state of Buddha Vajra Bearer.

In 1995, in response to requests from two translators, Lama Tcheucky and Lama Namgyal, on behalf of my foreign disciples, I, Karma Ngedon Chokyi Lodro, who holds the title of Bokar Tulku, wrote this at my home in Mirik Monastery. May it prove meaningful.[i]

[i] Zangpo, Ngawang. trans. Timeless Rapture: Inspired Verse of the Shangpa Masters. Snow Lion Publications. 2003. Ithaca, NY., Pg. 215-217.

his holiness the 16th karmapa on the nature of mind

In honor of the approaching 28th annual Kagyu monlam in Bodh Gaya I would like to share a pith instruction of His Holiness the 19th Karmapa Rangjung Rikpai Dorje. While every year is special, and every Kagyu monlam is truly a wonderous event, this year’s monlam coincides with the 900 year anniversary of the birth of the first Karmapa, Dusum Khyenpa. This is a moment to celebrate and praise the history of the Kamstang Kagyu Lineage and all of its wonderous lineage holders, siddhas, yogins and yoginis. Emaho! I am humbled to know that His Holiness the 17th Karmapa, Orgyen Drodul Trinley Dorje will be leading the prayers along with the leading lineage holders of the Kagyu lineage.

You can learn more about this year’s monlam, its schedule and special activities here.

His Holiness the 16th Karmapa on pointing out the nature of mind

Here, in the thick darkness of deluded ignorance,

There shines a vajra chain of awareness, self-arisen with whatever appears.

Within uncontrived vividness, unimpeded through the three times,

May we arrive at the capital of nondual, great bliss.

Think of me, think of me; guru dharmakaya think of me.

In the center of the budding flower in my heart

Glows the self-light of dharmakaya, free of transference and change,

that I have never been separate from.

This is the unfabricated wisdom of clarity-emptiness, the three kayas free of discursiveness.

This is the true heart, the essence, of the dharmakaya, equality.

Through relying on the display of the unfabricated, unceasing, unborn, self-radiance,

May we arrive at the far shore of samsara and nirvana- the great, spontaneous presence.

May we enter the forest of the three solitudes, the capital of the forebears of the practice lineage.

May we seize the fortress of golden rosary of the Kagyu.

O what pleasure, what joy my vajra siblings!

Let us make offerings to dharmakaya, the great equal taste.

Let us go to the great dharmadhatu, alpha purity free from fixation.

They have thoroughly pacified the ocean of millions of thoughts.

They do not move from the extreme-free ocean of basic space.

They posses the forms that perfect all the pure realms into one-

May the auspiciousness of the ocean of the protectors of being be present.

In the second month of the Wood Hare year (1976), [His Holiness] spoke these verses at Rumtek Monastery, the seat of the Karmapa, during the ground breaking ceremony for the construction of the Dharmachakra Center for Practice and Study.

Milarepa on the nature of mind

This is a particularly intimate and moving song of instruction by Milarepa for his student Gampopa. The imagery of a parent concerned for his child contributes to the sense of closeness between the teacher and student in this song, it also shows how subtle some of the maras (perceptual delusions) that we experience along the way can be. Milarepa as the tender father helps to point out some of the pitfalls that obscure the natural luminosity of the mind’s essential nature.

Following along with the parenting metaphor for a moment, I am reminded of a teacher who once reminded a friend and I that once one begins to meditate, no matter how much time spent in meditation, or its frequency, we should act as if we are pregnant; or we should know that we are pregnant with the innumerable qualities and benefits of Buddhahood. How long the gestation period will be is hard to know, but one day we will give birth to the clear and stainless realization of our mind. All it takes is to begin a meditation practice and examine what effects it has on our perception and our relative well-being; once we are pregnant with this potential awakening, we should guard ourselves against that which complicates and distracts our meditation practice. The tone that Milarepa sets in this song is gentle and supportive; how can we be this way with ourselves in our practice?

A Song of Instruction to Gampopa

By Milarepa

Son, when simplicity dawns in the mind,

Do not follow after conventional terms.

There’s a danger you’ll get trapped in the eight Dharma’s circle.

Rest in a state free of pride.

Do you understand this, Teacher from Central Tibet?

Do you understand this, Takpo Lhajey?

When self-liberation dawns from within,

Do not engage in the reasonings of logic.

There’s a danger you’ll just waste your energy.

Son, rest free of thoughts.

Do you understand this, Teacher from Central Tibet?

Do you understand this, Takpo Lhajey?

When you realize your own mind is emptiness,

Do not engage in the reasoning “beyond one or many”.

There is a danger that you’ll fall into a nihilistic emptiness.

Do you understand this, Teacher from Central Tibet?

Do you understand this, Takpo Lhajey?

When immersed in Mahamudra meditaion,

Do not exert yourself in virtuous acts of body and speech.

There’s a danger the wisdom of nonthought will disappear.

Son, rest uncontrived and loose.

Do you understand this, Teacher from Central Tibet?

Do you understand this, Takpo Lhajey?

When the signs foretold by the scriptures arise,

Do not boast with joy or cling to them.

There’s a danger you’ll get the prophecy of maras instead.

Rest free of clinging.

Do you understand this, Teacher from Central Tibet?

Do you understand this, Takpo Lhajey?

When you gain resolution regarding your mind,

Do not yearn for the higher cognitive powers.

There’s a danger you’ll be carried away by the mara of pretentiousness.

Son, rest free of fear and hope.

Do you understand this, Teacher from Central Tibet?

Do you understand this, Takpo Lhajey?[i]

[i] Songs and Instructions of the Karmapas. Nalandabodhi Publications. 2006. Pg. 25-26.

Anniversary of Bokar Rinpoche’s parinirvana

Today is the six-year anniversary of the parinirvana of Kyabje Bokar Rinpoche. With that in mind I want to share a prayer for the return of Bokar Rinpoche by His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama. May there be no hindrances in his swift return!!

A Prayer for the Swift Return of Kyabje Bokar Rinpoche

by His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama

From the empty, unimpeded play of dharmadhatu-awareness

The myriad objects of refuge abiding in oceans of pure realms

Perpetually radiate compassionate enlightened activity.

Grant your blessings that the intent of these aspirations is expediently fulfilled.

Treasury of the secret and profound teachings of the practice lineage,

Your wisdom having fully blossomed, with fearless confidence

You expound the essence of the dharma of definitive meaning.

Unrivaled supreme lama, please heed our call.

Upholder of the heart essence of the Victor’s teachings,

Benevolent nurturer of beings, we beseech you to continuously

Provide refuge to those endowed with faith and without protection.

Gazing upon us with compassion, may your incarnation swiftly appear!

By the potent waves of the authentic blessings of the peaceful and wrathful three roots,

Unencumbered by obstacles and unfavorable circumstances,

May the desired fruits of our intentions fully ripen and

May they continuously manifest in glorious abundance!

The illuminator of the practice lineage, Bokar Karma Ngedon Chokyi Lodro Rinpoche having quite suddenly entered the state of peace, his monastery and Khenpo Lodro Donyo with offerings have requested me to write a prayer for his swift return. Thus I, the Dalai Lama Tenzin Gyatso, a monk of Shakyamuni’s tradition, have written this on the 23rd day of the 7th month on the Wood Monkey year of the seventeenth cycle, September 7, 2004.

His Eminence Gyaltsab Rinpoche on Placing the Mind at the time of Death

Greetings! In keeping with the last post, I would like to continue along in a manner that accords with the way my recent trip to the Darjeeling and Sikkim areas unfolded. From the seat of the excellent Kyabje Bokar Rinpoche in Mirik, I journeyed to Palchen Choeling Monastic Institute, the seat of His Eminence Gyaltsab Rinpoche, in Ralang, Sikkim.

Nestled between the wonderful mountains of Tibet to the north, Nepal to the west, and Bhutan to the east, the site of the monastery is magnificent, inspiring and embued with peaceful beauty. To the south of the monastery is the retreat center, the largest in Sikkim, home to seventy-five retreatants engaged in the Karma Kagyu three-year retreat focusing on the Six yogas of Naropa. Behind the retreat center is a mountain upon which was the hermitage of a lama named Drubthob Karpo, known for his ability to fly. Nearby are the monasteries of Tashiding (built in the 16th century) and Pemayangtse, and many sites visted by Guru Rinpoche.

I had come to Ralang for an annual period of retreat and to continue to receive a little bit of instruction from His Eminence. He had just returned from Gyuto where he had spent the previous month or so with His Holiness the 17th Karmapa. Fortunately, a few days after my arrival Rinpoche told me that he would be bestowing the complete series of empowerments for the traditional three-year retreat to a group of monks from Mirik and Phodong; he said that I could sit in with the monks and recieve the empowerments as well. This seemed particularly auspicious to me as I would be with monks from Bokar Rinpoche’s monastery (my extended dharma family) and Phodong (a small rural gompa founded during the lifetime of the ninth Karmapa by the Chogyal of Sikkim who then offered it to the ninth Karmapa). Phodong gompa was a favorite of Ani Zangmo, Pathing Rinpoche and Bhue Rinpoche, and through them Phodong came to occupy a special place in my heart. I couldn’t think of any better company to have for such an endeavor.

Towards the end of my month-long stay at Palchen Choeling Monastic Institute I had the good fortune to ask Rinpoche about placing the mind at the point of death, as well as issues surrounding lay people offering prayer and ritual for others. I’ve included Rinpoche’s teaching regarding the placement of the mind at the point of death towards the end of this post following two descriptions of the Gyaltsab Rinpoche incarnation lineage.

As for the issue of lay people conducting prayers and for rituals for others, Rinpoche reiterated the position held by Khenpo Lodro Donyo Rinpoche, specifically that it is fine for lay people to engage in such activities, and that one should do whatever practices they know and or are qualified to practice. To be frank, this question was generally met with incredulous glances- it seems a little strange to ask “is it okay if I do something with the intention of benefitting another being?”. In any case, Rinpoche was both supportive and interested, as well as quite curious as to what the response was like to changchub.com.

So, here’s some history of His Eminence the 12th Goshri Gyaltsab Rinpoche…

The reincarnation lineage of the Goshri Gyaltsab Tulkus:

The website for Karma Triyana Dharmachakra, the North American seat of His Holiness the 17th Karmapa (http://www.kagyu.org/) describes the reincarnation lineage of the Gyaltsab Rinpoches as follows:

The twelfth Gyaltsab Rinpoche was born in Central Tibet in Nyimo, near Lhasa. From generation to generation his family was well-known for giving rise to highly developed yogis who achieved their attainments through the recitation of mantras and through Tantric practices. Gyaltsab Rinpoche was one such offspring who was actually recognized by His Holiness the Sixteenth Karmapa before he was born.

In 1959, Gyaltsab Rinpoche made the journey to Sikkim with His Holiness. He remained for a while with His Holiness’ settlement group in the old Karma Kagyu monastery, which had been built at Rumtek during the time of the ninth Karmapa. In the early 1960’s, Rinpoche received several very important initiations from His Holiness.

After these initiations, his father felt that his child should receive a modern education in English, so he took him to the town of Gangtok to study. However, with his extraordinary vision of what would be truly beneficial, the young Rinpoche chose to study Dharma in His Holiness’ monastery instead of remaining at the school. Just after midnight one night he left his residence in Gangtok and walked the ten miles to Rumtek alone. At sunrise he arrived at the new Rumtek monastery. When he first appeared, all the monks who saw him were surprised at his courage, and most respectfully received him in the main temple, where His Holiness welcomed him. Despite the conflict of ideas between his father and the monks about his education, he began to study the Mahayana and Vajrayana teachings of the lineage with three other high Rinpoches.

In Rumtek these four Rinpoches studied basic ritual rites and texts with private tutors. They also studied Mahayana philosophy through investigating numerous commentaries by early well-known Tibetan teachers and scholars, and teachings by masters of Indian Buddhism whose texts had been translated into the language of Tibet many centuries ago.

In previous lifetimes all four of these Rinpoches have been great teachers and lineage holders. In each of their lifetimes, one complete and unique example had been set up, beginning from a childhood learning reading and writing and going through the whole process of study, with a youth spent in discipline leading to a fully ripened human being.

Since the time of Shakyamuni Buddha, we are taught that we each must become a truly complete human being. For us as human beings the truth is that we develop the fruit of both good and evil by virtue of our own view, practice, and habitual reactions. This fruit of our own actions on both the physical and mental levels can be either positive or negative. As long as we are ordinary human beings we must deal with the truth of that experience.

Great teachers like Gyaltsab Rinpoche show a perfect example to human beings and especially to those who can relate to the idea that one is responsible for oneself and for others as well, and that no one else is responsible for how we spend our lives, whether we build for ourselves experiences of happiness or suffering. They show us that the difference between an enlightened and an ordinary human being is not one of wealth, title or position, but only one of seeing the present reality of mind experienced at this moment.

The history of the lineage of Gyaltsab Rinpoches:

The Gyaltsab Rinpoches have always been the Vajra Regents of the Karmapas and caretakers of the Karmapa’s monasteries.

Gyaltsab Rinpoche, through his long line of incarnations, has been known for being an expert in meditation.

Goshir Gyaltsab Rinpoche is the emanation of the Bodhisattva Vajrapani. In the past, Rinpoche incarnated as Ananda, the disciple of the Buddha Shakyamuni who had perfect memory and was responsible for reciting all of the sutras (teachings) of the Buddha before the assembly. Therefore Ananda was responsible for keeping all the words of the Buddha perfectly intact.

Gyaltsab Rinpoche also incarnated as one of the main ministers of the Dharma King Songtsen Gampo of Tibet. He was also Palju Wangchuk, one of the twenty-five principle disciples of Guru Padmasambhava. During Milarepa’s lifetime, Rinpoche appeared as Repa-zhiwa U.

The 1st Gyaltsab Rinpoche Paljor Dondrub (1427-1489) received the glorious title Goshir from the Emperor of China. He took birth in Nyemo Yakteng. His Eminence, who was cared since childhood by the Karmapa, was appointed as the Karmapa’s secretary and regent at fourteen years old. He received the complete transmission of the lineage from the Karmapa, Jampal Zangpo, and the 3rd Shamar Rinpoche. He became the main teacher to the next Karmapa.

The 2nd Gyaltsab Rinpoche Tashi Namgyal (1490 – 1518) received the Red Crown which liberates on sight from the Karmapa. This Red Crown indicates the inseparability of the Karmapa and Gyaltsab Rinpoche, and also indicates that their enlightened minds are equal in nature. Rinpoche recognized the 8th Karmapa and was responsible for his education.

The 3rd Gyaltsab Rinpoche Drakpo Paljor (1519-1549) took birth south of Lhasa and was appointed as the Karmapa’s main regent.

The 4th Gyaltsab Rinpoche Dragpa Dundrub (1550-1617) was also born near Lhasa and received the transmission of the lineage from the Karmapa and the 5th Shamarpa. He was renown for his commentaries and attracted hundreds of disciples.

The 5th Gyaltsab Rinpoche Dragpa Choyang (1618-1658) was enthroned by the 6th Shamar Rinpoche. He spent the majority of his life in meditation. He was also very close to His Holiness the 5th Dalai Lama, as they were strongly connected spiritual friends. Before the 10th Gyalwa Karmapa fled Tibet due to the Mongol invasion, the Karmapa handed over the mantel of the lineage to Gyaltsab Rinpoche.

The 6th Gyaltsab Rinpoche Norbu Zangpo (1660-1698) was enthroned by the 10th Karmapa, after taking birth in Eastern Tibet. He meditated very deeply and wrote numerous commentaries.

The 7th Gyaltsab Rinpoche Konchog Ozer (1699-1765) took birth near Lhasa and was enthroned by the 12th Karmapa. He became one of the main root gurus of the 13th Karmapa, and transmitted to the Gyalwa Karmapa the lineage.

The 8th Gyaltsab Rinpoche Chophal Zangpo (1766-1817) had the 13th Gyalwa Karmapa and the 8th Situ Rinpoche as his main teachers. He became a renown master of meditation and accomplish high states of realization.

The 9th Gyaltsab Rinpoche Yeshe Zangpo (1821-1876) and the 10th Gyaltsab Rinpoche Tenpe Nyima (1877 – 1901) closely guarded the precious transmissions of the Kagyu lineage: receiving them and passing them onto the other lineage masters. Both spent their lives in deep meditation.

The 11th Gyaltsab Rinpoche Dragpa Gyatso (1902-1949) was recognized by the 15th Gyalwa Karmapa and transmitted the lineage.

The 16th Karmapa Rangjung Rigpe Dorje recognized the present and 12th Gyaltsab Rinpoche while He was still in his mother’s womb. His parents were from Nyimo, near Lhasa. Soon after his recognition in 1959, His Eminence fled into exile with the 16th Gyalwa Karmapa.

The Gyalwa Karmapa carried Rinpoche on his back while traveling across the Himalayas into exile. He soon settled at Rumtek Monastery in Sikkim and received the necessary transmissions.

His Eminence learned the dharma with the other heart sons of the Karmapa such as Jamgon Kongtrul Rinpoche and Tai Situ Rinpoche. Like most of his incarnations, he spends his life in meditation and taking care of the seat of the Karmapa. He currently in Sikkim and is the Regent there representing the lineage. He oversees the activities and functions of Rumtek and at his own monasteries, such as Ralang, in Sikkim.

In 1992, Gyaltsabpa and Tai Situpa enthroned the 17th Gyalwa Karmapa in Tibet. The Karmapa has since fled to India and Gyaltsab Rinpoche will help prepare for His Holiness the Karmapa’s return to Rumtek.

Like Situ Rinpoche, Gyaltsab Rinpoche is one of the main teachers of HH the 17th Gyalwa Karmapa and already has bestowed transmissions (from the Rinchen Terdzo, among others) to His Holiness.

As mentioned earlier, I had the opportunity to ask His Eminence about how we should place our minds at the time of death. It seemed to me that this would be a good topic to be able to transmit on Ganachakra as it is both personally relevant (we will all eventually die, and we generally do not know when that will occur), and a very worthy teaching to transmit to others. From the standpoint of chaplaincy, I feel that this instruction is very useful. As is true with most profound meditation instructions, this instruction is beautifully simple, and quite short, but upon reflection on the meaning implied in Rinpoche’s instruction, it captures the natural ease with which resolution at the point of death has the ability to transform the tonality of one’s entire life.

With that said, it is with great pleasure and enthusiasm that I share with you Rinpoche’s thoughts on what one can do as they are dying, or faced with their impending death; how can one place the mind in the face of such an experience?

His Eminence Gyaltsab Rinpoche on Placing the Mind at the time of Death

When one is dying, or about to die, and, they are Buddhist, it is best to practice whatever practices they know. It is important in this manner to reinforce a dharmic outlook- to experience dharma as best as one can.

If one is not Buddhist, then it is of immense benefit to contemplate loving kindness or compassion. In doing this, one opens themselves up to the direct experience of others. In developing a compassionate outlook at the point of death it is possible to transform the habitual tendencies of self-centered outlook that creates the causes of suffering, into the potential for great spiritual gain. In fact one can eliminate great amounts of negative karma through such meditation or contemplation.

There is a story from the life of the Buddha, in which the Buddha was standing by the side of a river. In this river was a great alligator- this alligator when he looked up towards the Buddha, was transfixed by the radiant appearance of the Buddha’s face and kept staring at it. For a very long time, the alligator kept looking at the Buddha’s face, amazed at how peaceful he appeared. After some time the alligator died- but as a result of the peaceful calm feelings it experienced as a result of staring at the Buddha’s face for such a long time, the alligator was born in one of the heaven realms as a god, with all of the faculties and conditions to practice the dharma.

In this way, the moment of death is quite a powerful and meaningful period where one can make quite a difference in the quality of their habitual perceptions up to that time.

Khenpo Lodro Donyo Rinpoche on Practice for Others

I recently arrived home from a wonderful and highly recharging six-week period in India. While there, I split my time between Mirik, near Darjeeling, where Bokar Ngedhon Chokhorling (Kyabje Bokar Rinpoche’s seat in India) is located, Ralang, Sikkim, where His Eminence Gyaltsab Rinpoche’s seat-in-exile is located, and in Varanasi/Sarnath.

As I posted before I left, I had intended in requesting the ven. Khenpo Lodro Donyo Rinpoche, the dharma brother and direct heart-son of Kyabje Bokar Rinpoche, for some thoughts regarding the way we may be of benefit for people through the practice of ritual and the recitation of prayers and mantras for those who are sick, dying or who have passed away. While I was in Mirik, an old friend and former professor emailed me regarding the launch of changchub.com. He was quick to offer compliments regarding the structure of the site, and also expressed: “offering prayers on the behalf of others is something deeply established in the monastic tradition of the Himalayas; however, it is quite new to our culture.” Then he posed an excellent question: is it time for this in the west, and may such prayers be offered by lay people as well as monks?

This question is a good one. Thank you for bringing it up Robert!

For me, it raises questions in terms of what the true difference between the lay practitioner and the ordained practitioner may actually be- it reminds me of both the Vimalakirti Sutra and also the spirit of enquiry expressed in Vipassana (Tib. Lhaktong) meditation.

So, what is the difference between lay and ordained? Additionally, the question can be extended to what is the difference between “eastern” and “western” cultures?

Clearly, the goal of reflecting on these questions in an open way is not to carelessly toss the relative differences aside, as wonderful beauty exists in both lay practice with its endless possibilities for practice, as well as that of the cloistered support of the ordained sangha member. Then there is the natural beauty of the difference between being from Brooklyn and Darjeeling, for example.

However, perhaps it is possible to see that despite the apparent differences the same dharma is shared; the nun and the householder share the same essence- the root of the essential sameness is the point. At least that’s the way I came to formulate my answer to the question posed. We bring the tone and flavor to our own actions- a monk or nun with a busy distracted mind is the same as a layperson with a similarly distracted mind. Likewise, a layperson with clear penetrating recognition of the suchness of their mind is no different from a nun or monk with a similar view. That said, the ordained sangha performs the vital role of preserving the actual lineage- but it should not be forgotten that as lay-people, when we receive instructions and practice them, we too are preserving a practice lineage.

As for offering prayers or performing ritual practice for others; making such offerings and dedicating the merit of practice for others is of immense benefit to the recipient. It helps to create the conditions of peace and the alleviation of suffering; it is an act of kindness, a reminder of our interconnectedness, and an act of skillful-means. It seems to me to be the fresh-faced other-side-of-the-coin that is meditation practice; something that is often seen as solitary, often aimed at individual personal spiritual development, and perhaps in the West presented in an all too myopic fashion. Maybe we could benefit from being shaken up a bit and made to exercise more of the compassion side of the wisdom/compassion relationship…

I would like to return to this subject in the near future, as I feel that it’s an important one, but for now, I’d like to share Khenpo Rinpoche’s wonderful instructions.

As I had previously intended on asking Khenpo Rinpoche what should be done to benefit those who are sick, dying, or have passed away, on July 5th, I happily took this extra question to him as well. There’s a great bio of Khenpo Rinpoche at the gompa’s website: http://www.bokarmonastery.org, if you’d like more information about him, the late Kyabje Bokar Rinpoche, and Bokar Ngedhon Chokhorling.

Ven. Khenpo Lodro Donyo Rinpoche on Practice for Others

When one is going to die, you should try your best to pacify the dying person’s mind. Try to bring peace. If the person is Buddhist then you can recite the lineage masters’ names, or for example “Karmapa Chenno” (Karmapa think of me), as well as one’s own root master’s name. If the person has died, you can whisper these in the person’s ear in a pleasing voice. You can also recite the names of various Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, for example, Amitabha (mantra: Om Ami Dhewa Hri), or Chenrezig (mantra: Om Mani Padme Hum), or some other mantra; whatever you know.

These are very important. You see, when one is dying as well as for the person who has passed away, after their death, while in the Bardo state hearing the names of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas and lineage masters makes one recall the Dharma; it is like a positive habit where one remembers the dharma and then can easily be liberated. This is very important.

If the person is non-Buddhist you can see if the person likes hearing the names and mantras of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas or not. If one likes to hear the names and mantras of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas and they are not Buddhist that’s fine.

If one dislikes hearing such names or mantras then you shouldn’t say them, but mentally you can visualize or recite the names and mantras of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas to help the person who is either sick, dying, or has died. You should also visualize yourself as Chenrezig or Amitabha while your mind and the mind of the deceased person are merged, and then meditate. Also, you should do tonglen. You see, you should send your happiness, your virtuousness, your peace, to the person who has passed away- expelling their sorrows, fear, and unhappiness. This is an excellent time to do tonglen practice.

Without saying anything, you can also mix your mind with the mind of the person who has died and rest in the Mahamudra state.

These things, along with meditation on love and compassion are the best things that you can do.

When one is sick you can do Sangye Menla (Medicine Buddha), Lojong, and others, Guru Yoga, Dorje Sempa (Vajrasattva)- anything that purifies. You should try your best to examine what is best for the particular person- check the situation.

Basically, any practice can be done for the person who has died. Often though, it is good to do Amitabha so that the person may be reborn in Amitabha’s pure land. You can do the Dewachen Monlam many times, for forty-nine days, or three weeks, or one week even- or alternatively you should do the longer Amitabha practice if you know it and have the time.

All of these things will help.

[Note: While Rinpoche and I were talking, I specifically brought up to him the fact that for some in the West the dedication of prayer or ritual offerings for the benefit of those who are sick, dying or have died, may seem new as it tends to be less emphasized when one normally thinks of Dharma practice, and I asked if it is okay to perform such activities. Khenpo Rinpoche was very enthusiastic in his response, saying that indeed anyone can do practice for others. One can do whatever practices that they know. The most important thing is that one is trained in the practices that they are doing for others- this means that if the practice requires an empowerment and reading transmission, then these must be obtained, as well as whatever subsequent instructions are necessary to perform the practice. Practicing for others should not be seen as limited to ordained sangha members. He was very definitive in expressing this.]

May this be of benefit!

Maitripa on mahamudra

Today I’d like to share an essential instruction of mahamudra by the great Indian mahasiddha Maitripa. Maitripa was a student of the mahasiddha Shavaripa, an early master of the Mahamudra lineage, and originator a mahakala transmission lineage based upon his visionary experiences in a cave on a mountain just north east of Bodh Gaya. This site is also the location of Śītavana charnel ground, also known as Cool Grove charnel ground. It was commonly believed that Cool Grove was a place frequented by ghosts, a place where strange things happened, and where wild animals would come and eat the remains of people who were brought here after death. Śītavana is listed as one of the eight great charnel grounds. It was a place for profound meditation, but also a place of danger.

Maitripa was one of the central teachers of Marpa Lotsawa, the great Tibetan translator who brought the early Kagyu lineage instructions from India to Tibet. Maitripa’s mahamudra instruction was unique and goes back to the great siddha Saraha, who is credited with being the source of the Mahamudra lineage. It is believed that Maitripa spent a good deal of time in the foothills of the eastern Himalayas, near the town of Mirik, in West Bengal.

Maitripa’s Essential Mahamudra Verses

To innermost bliss, I pay homage!

Were I to explain Mahamudra, I would say—

All phenomena? Your own mind!

If you look outside for meaning, you’ll get confused.

Phenomena are like a dream, empty of true nature,

And mind is merely the flux of awareness,

No self nature: just energy flow.

No true nature: just like the sky.

All phenomena are alike, sky-like.

That’s Mahamudra, as we call it.

It doesn’t have an identity to show;

For that reason, the nature of mind

Is itself the very state of Mahamudra

(Which is not made up, and does not change).

If you realize this basic reality

You recognize all that comes up, all that goes on,

as Mahamudra,

The all-pervading dharma-body.

Rest in the true nature, free of fabrication.

Meditate without searching for dharma-body—

It is devoid of thought.

If your mind searches, your meditation will be confused.

Because it’s like space, or like a magical show,

There is neither meditation or non-meditation,

How could you be separate or inseparable?

That’s how a yogi sees it!

Then, aware of all good and bad stuff as the basic reality,

You become liberated.

Neurotic emotions are great awareness,

They’re to a yogi as trees are to a fire—FUEL!

What are notions of going or staying?

Or, for that matter, “meditating” in solitude?

If you don’t get this,

You free yourself only on the surface.

But if you do get it, what can ever fetter you?

Abide in an undistracted state.

Trying to adjust body and mind won’t produce meditation.

Trying to apply techniques won’t produce meditation either.

See, nothing is ultimately established.

Know what appears to have no intrinsic nature.

Appearances perceived: reality’s realm, self-liberated.

Thought that perceives: spacious awareness, self-liberated.

Non-duality, sameness [of perceiver and perceived]: the dharma-body.

Like a wide stream flowing non-stop,

Whatever the phase, it has meaning

And is forever the awakened state—

Great bliss without samsaric reference.

All phenomena are empty of intrinsic nature

And the mind that clings to emptiness dissolves in its own ground.

Freedom from conceptual activity

Is the path of all the Buddhas.

I’ve put together these lines

That they may last for aeons to come.

By this virtue, may all beings without exception

Abide in the great state of Mahamudra.

Colophon

This was Maitripa’s Essential Mahamudra Instruction (in Tibetan: Phyag rgya chen po

tshig bsdus pa), received from Maitripa himself and translated by the Tibetan translator

Marpa Chökyi Lodrö.

© Nicole Riggs 1999. Reproduction welcome

if not for profit and with full acknowledgement.

![Validate my RSS feed [Valid RSS]](valid-rss-rogers.png)