on the importance of the teacher

I recently spent time considering the importance of my teachers and how fortunate I feel to have received just a portion of the stream of their experience through instruction. The importance of the teacher, whether we call him or her lama or guru, is central- for where would we be without their guidance, their compassion, and their wisdom? Through the openness that we allow ourselves to have with our teachers, a connection of transmission occurs through which we can experience our own fullness and Buddha potential, just as they themselves have done.

I’ve found three passages that help illustrate this point:

This first one is entitled Hail to Manjushri, it was written by the third Karmapa Rangjung Dorje (1284-1339).

Hail to Manjushri!

All phenomena are like illusions,

though absent they appear to exist;

wise indeed are those who cognize them

within the ever-present unborn.

If you perceive the glorious guru

as a supremely enlightened being,

indivisible from your own mind,

you will receive blessings and strength.

If you, without ceasing, propel the flow

of channels, wind energies, and vital drops-

the nexus of interdependent factors-

the stains of self-love will be swiftly cleansed.

The manifold states of nonconception-

clarity and bliss- I place on the path

of nonapprehension, like patterns in water,

then the true mode of being will be definitely seen.[i]

This next song is from the larger section of the collected songs of Milarepa (1052-1135). Milarepa, one of the greatest yogins tha Tibet saw was the heart student of Marpa Lotsawa. Milarepa’s endurance in his practice, and the joy with which he taught is truly remarkable. This song is a portion of the larger song-story called The Song of a Yogi’s Joy:

The Guru, the disciple, and the secret teachings;

Endurance, perseverance, and the faith;

Wisdom, compassion, and the human form;

All these are ever guides upon the Path.

Solitude with no commotion and disturbance

Is the guide protecting meditation.

The accomplished Guru, the Jetsun,

Is the guide dispelling ignorance and darkness.

Faith without sorrow and weariness

Is the guide which leads you safely to happiness.

The sensations of the five organs

Are the guides which lead you to freedom from “contact.”

The verbal teachings of the Lineage Gurus

Are the guides which illustrate the Three Bodies of the Buddha.

The protectors, the Three Precious Ones,

Are the guides with no faults or mistakes.

Led by these six guides,

One will reach the happy plane of Yoga-

Abiding in the realm of Non-differentiation

In which all views and sophisms are no more.

Remaining in the realm of self-knowledge and self-liberation

Is indeed happy and joyful;

Abiding in the valley where no men dwell,

With confidence and knowledge, one lives in his own way.

With a thundering voice,

He sings the happy song of Yoga.

Falling in the Ten Directions is the rain of fame;

Brought to blooming are the flowers and leaves of Compassion.

The enterprise of Bodhi encompasses the Universe;

The pure fruit of the Bodhi-Heart thus attains perfection.[ii]

The third passage is from Gampopa (1070-1153), one of the two main students of Milarepa, and the first to combine the ear-whispered teachings of Milarepa with the Kadampa monastic tradition, thus institutionalizing the Kagyu lineage as a generally monastic lineage. This passage comes from Gampopa’s Precious Garland of the Supreme Path, a wonderful instruction manual of practical advice from this special master. What follows is his description of the first thing that one should rely on as we tread the path, from the third portion of the text entitled, Ten Things Upon Which To Rely:

The first thing on which we must rely is a holy guru who possesses both realization and compassion. The lama must possess realization because a teacher who has no realization or actual experience is like a painting of water, which cannot quench our thirst, or a painting of fire, which cannot warm us. As well, a lama must possess compassion. If the lama merely has realization but has no compassion, he or she cannot teach and will not help sentient beings develop virtuous qualities and relinquish defects. Thus the first thing ton which we must rely is a lama who possesses both realization and compassion.[iii]

I hope that these passages contribute to a sense of connection and warmth with our teachers, and I hope that this connection helps foster inspiration. May this inspiration translate into diligent practice, and through this practice may we fully realize the essence of our teachers’ instructions. May we develop the same stainless conduct as our teachers! May we too raise the victory banner in the citadel of enlightenment!

May the activities of his Holiness the 17th Karmapa flourish and may all obstacles naturally dissolve into emptiness. May his life be long, and may the compassionate wisdom of his example be known to all beings!

[i] Jinpa, Thubten and Elsner, Jas, trans. Songs of Spiritual Experience. Shambala Publications, 2000. Pg. 157.

[ii] Chang, Garma CC.trans. The HUndered Thousand Songs of Milarepa. Shambala Publications,1999. Pg. 80-81.

[iii] Khenpo Karthar Rinpoche. The Instructions of Gampopa. Snow Lion, 1996. Pg. 22.

on pacifying, enriching, magnetizing and subjugating…

I recently attended a long weekend retreat on the Five Remembrances held by the New York Zen Center for Contemplative Care. It was wonderful to have time at the Garrison Institute to reflect upon these five essential points:

I am of the nature to experience old age, I cannot escape old age.

I am of the nature to experience illness, I cannot escape illness.

I am of the nature to experience death, I cannot escape death.

I am of the nature to experience loss of all that is dear to me, I cannot escape loss.

I am the owner of my actions. They are the ground of my being, whatever actions I perform, for good or ill, I will become their heir.

The Five Remembrances come from the Upajjhatthana Sutra which could be translated as The Sutra of Subjects of Contemplation. You can hear the teaching of the Five remembrances as found in the Upajjhatthana Sutta read by Kamala Masters here, or read a portion of the sutta translated by Thanissaro Bhikkhu here.

The Buddha’s discourse on the Five Remembrances resembles the realization that young Prince Siddhartha had concerning his recognition that we are all subject to birth, sickness, old age, death, and all of the forms of suffering associated with each phase of our existence. In the reading of the sutta by Kamala Masters, the Buddha points out that the first four Remembrances serve us well to return our focus onto the primacy of impermanence; doing so is a remedy towards arrogance, over-confidence, and conceit.

I will become sick. I will become old. I will experience loss. I will die. There is nothing that I can do to change this. When that happens, as this whole existence plays out, my only companion who remains with me throughout is the collection of my actions.

The Fifth Remembrance, which relates to our actions, the quality of our actions, or karma, colors the experience of each facet of our being. It can be the root of our liberation, or the hard kernel from which our suffering manifests. I’d like to take a moment to explore the Fifth remembrance, our actions, in a general sense and then look a little more specifically at action from the Vajrayana buddhist perspective, especially as it relates to actions of pacifying, enriching, magnetizing and subjugating.

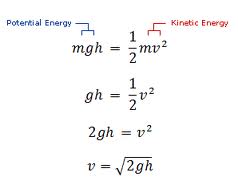

Action, movement, friction, trajectories, potential energies. These can easily refer to different forces and dynamics involved within the study of physics, which at close glance looks like a wonderful symbolic structure parallel to aspects of Buddhism, and yet as qualities they easily also connect to our behavior. Our behavior is composed of reactions or responses to the events around us, how we see the play of phenomena unfold before our very eyes. The quality of our perspective acts to determine the flavor of our actions, and the quality of our actions affects the continuum of our perspective. The more self-involved our perspective is, the more our actions involve the preservation and protection of self interests. The more we act to preserve and protect self-interests, the more easily we may think that others or events may be hindering our self-interests. Likewise, a more expansive perspective affords us the ability to act in a more expansive way. When we act with a larger concern for others’ well being, our ability to see the interrelatedness of self and other allows more clarity and more peace.

As we pass through this life, a conditioned existence that has been flavored by past events, the habits of reacting to the display of phenomena around us (our daily lives) often become stronger and more ridgid. The phrase goes: Actions speak louder than words. This seems right, but it’s amazing how we use thousands of words to hide or cover up and beautify our actions. Such elaborate verbal adornments so that we can feel okay about how we are right now.

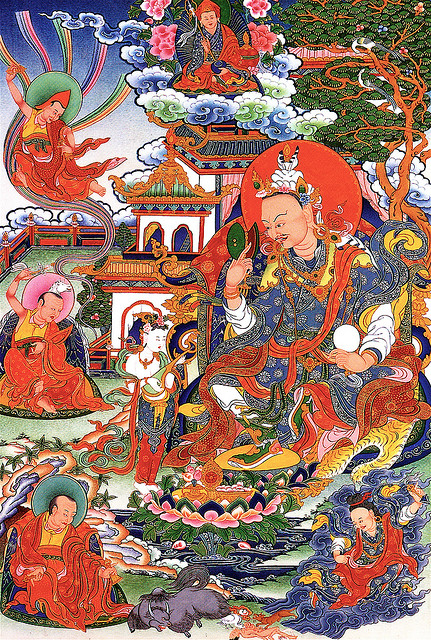

The above image is that of Senge Dradrok, or Lion’s Roar, one of the eight manifestations of Guru Rinpoche. Guru Rinpoche took this form in Bodh Gaya when he came to debate and challenge a group of five hundred non-Buddhist teachers who were trying to disprove the Buddha’s teachings. Guru Rinpoche won the debate and “liberated” all of them with a bolt of lightening- most of the village where the non-buddhists were staying was destroyed, those who survived became converts to Buddhism. This type of story is not so unique. The life story of the Mahasiddha Virupa and many others contain descriptions of such events- they are powerful descriptions of activities that certainly appear to run counter to the typical notion of what buddhist behavior is thought to be. This energy of wrathful subjugation, while not generally an everyday occurrence has it’s place- this hot humid searing energy is needed from time to time to remove impediments towards our spiritual growth.

How can we touch the quality of Senge Dradrok within ourselves? What does it feel like to be him, or Mahakala, Vajrakilya, or Palden Lhamo? What is the focus of these energies? How can we completely liberate the hundreds on non-dharmic impulses within us like Senge Dradrok?

In another form, that of Nyima Ozer, or Radiant Sun, Guru Rinpoche displayed himself as Saraha, Dombi Heruka, Virupa, and Krishnacharya, some of the most well-known Indian proponents of tantric Buddhism. While in this form Guru Rinpoche spent time in the eight great charnel grounds and taught Secret Mantra (tantric Buddhism) to the dakinis, while binding outer gods as protectors of his secret teachings. This is an act of magnetizing, drawing towards him the dakinis and protectors of his treasured teachings, spreading the dharma in the form of may important masters. In the form of a tantric master his intensity and use of whatever arises as a teaching tool captures the great energy deeply-seated within through which magnetizing activity becomes manifest. It seems that essential to the quality of magnetizing is the general awareness of skillful means; knowing just when to act in a way to be of the most benefit in any given situation.

Yet another activity form of Guru Rinpoche appears as Pema Gyalpo, or Lotus King. In the form of Pema Gyalpo, Guru Rinpoche taught the inhabitants Oddiyana the Dharma as he manifested as the chief spiritual advisor for the King of Oddiyana. His selfless dedication and compassionate timely teaching activity enriched all who came into contact with Pema Gyalpo such that they became awareness-holders in their own right. This enriching activity has untold benefits; the effects of the nurturing support that Pema Gyalpo displayed through his teaching activity caused an incredible expansion of the Dharma in Oddiyana.

This final image is of Guru Rinpoche as himself, who among most Himalayan Buddhists is considered the second Buddha in the sense that he is credited with bringing Buddhism to Tibet. While he wasn’t technically the first, he was the first to introduce tantric Buddhism in a way that took hold, and is credited with helping to construct the first Buddhist monastery in Tibet. A dynamic teacher, Guru Rinpoche embodied all of the qualities of his eight manifestations and countless others. Through the expression of his life Guru Rinpoche was able to display pacification, enriching, magnetizing, and subjugation both in Oddiyana, India, Bhutan, Tibet, and even now.

Within tantric Buddhist literature we often find references to the importance of adopting the behavioral modalities of pacifying, enriching, magnetizing, and subjugating as illustrated by the eight manifestations of Guru Rinpoche. These activities were seen as extremely important as they pertain to embodying the qualities of a variety of tantric buddhas as well as the essence of Buddhahood in all emotions. Furthermore, they are utilitarian activities, they support and enrich and massage us as we travel the path of enlightenment. References to these activities can be found in the translations of various tantric texts by a variety of outstanding Buddhist scholars such as David Snellgrove, David B. Gray, Christian K. Wedemeyer, and Vesna A. Wallace to name a few. One can also rely upon the namthars (liberation stories) of many Indian and Himalayan Buddhist Siddhas to feel the range of possible human action on both inner and outer levels of being. Finally, our practice sadhanas contain a wealth of wisdom and guidance- the words in sadhanas are not arbitrary- and they often capture with great clarity the essence of dharma being.

We are aging. We will experience illness. We will die. We will experience loss. Our actions are our ground and we are the owners of our actions. That this is the case is undeniable. We cannot change the first five certainties, but we can change our actions. Our actions, and the related ability to perceive, directly determine how we relate qualitatively towards aging, illness, death, and impermanence. Let’s apply the depth and range of possibilities as exemplified by Guru Rinpoche and other Buddhist Siddhas- lets refine, strengthen, expand, and deepen our relationships with ourselves, with the world around us and with our experience of mind. We are completely capable of manifesting in this way- it doesn’t matter if we wish to embody Tilopa, Virupa, Tsongkhapa, Taranatha, Machik Labron, or Garab Dorje, we are all capable of touching their essential being. No one can do this for us. At the end, as we lay dying, who can really blame for our shortcomings?

Sacred geography: external, internal and in-between

As part of my CPE (Clinical Pastoral Education) training with the New York Zen Center for Contemplative Care we have been exploring aspects of Jungian psychology especially as it relates to symbols and images. We recently finished a great week of classroom experience which included a conversation with Morgan Stebbins, the Director of Training of the Jungian Psychoanalytic Association, a faculty member of the C.G. Jung Foundation of New York, and a long time student of Buddhism. Stebbins’ presentation on Symbol and Image was dynamic and quite moving- he embodies a depth and conviction that I find compelling. In addition to this, Stebbin’s visit to our class came at a point when I’ve been playing around with writing a blog post about sacred geography. Very timely indeed.

As part of my CPE (Clinical Pastoral Education) training with the New York Zen Center for Contemplative Care we have been exploring aspects of Jungian psychology especially as it relates to symbols and images. We recently finished a great week of classroom experience which included a conversation with Morgan Stebbins, the Director of Training of the Jungian Psychoanalytic Association, a faculty member of the C.G. Jung Foundation of New York, and a long time student of Buddhism. Stebbins’ presentation on Symbol and Image was dynamic and quite moving- he embodies a depth and conviction that I find compelling. In addition to this, Stebbin’s visit to our class came at a point when I’ve been playing around with writing a blog post about sacred geography. Very timely indeed.

“What does sacred geography have to do with me?” one might ask. I would answer, “Everything”.

Within the framework of Buddhism geography and therefore pilgrimage, has come to be something of an important phenomena. Certainly this is not anything unique to Buddhism; we have a tendency to want to return to places that are significant for us. Sometimes there is spiritual significance, sometimes it is societal, and most often it is interpersonal. An example of these would be making the Hajj if you were Muslim, perhaps visiting Washington D.C., or taking your children there so that they could appreciate the way that our nation governs itself, and perhaps the place where one’s parents were born, or where they died. Geography allows us to honor the meaning that we value in our lives. We live within time and space, and within the latitude and longitude that time and space afford us, we intentionally (and even unintentionally) plot the course of our lives and identities within their dynamics. How many times has a particular season or even date reminded us of an event that occurred in the past around the same time? My root teacher passed away on Christmas eve over a decade ago, and I am always reminded of that great loss whenever Christmas approaches. On the other hand, the Fall months feel like a time of rich growth for me- they always have, and for some reason these months continue to prove to be significant for me. These are two examples of how I plot meaning within my experience of time.

In most faiths pilgrimage has become something that one engages to touch the past; it is a means to feel the link of those who have come before us and charge the present moment with their power. It can be the Wailing Wall, St. Peters, the Kabba, Bodh Gaya, a sacred mountain, river, the ocean, a tree and it can also be imagined- something symbolic, a living pulsating image such as a mandala.

According to the Mahaparinirvana Sutra, the Buddha predicted that students of the path would visit the place of his birth, his enlightenment, where he first taught, and where he would die. He stressed that this may be something that one does if they want to, if it brings meaning, inspiration, and context to their path. It was a suggestion, not a directive, and ultimately a very insightful reading of how we relate to time and space.

Within Vajrayana, or tantric Buddhism, pilgrimage appears in a more visionary manner. In addition to the four major sites associated with the Buddha’s life, various pithas, or ‘seats’ (places of power and meaning associated with the dissemination of Buddhist tantra) became included into various lists of sacred places. For example, there are twenty-four pithas throughout the Indian sub-continent that are associated with the places where the Buddha revealed himself as Chakrasamvara and taught the cycle of Chakrasamvara and related practices. The pithas, while relating to actual places, also correspond to places within our bodies that have an internal energetic significance. The exact location of these pithas vary from tradition to tradition, but there is a relative constancy of the mirroring of external and internal meaning in relation to these sites. In some ways, and according to some teachers, pilgrimage can be done without ever leaving where you are as all of the major pithas exist within the matrix of our energetic body. This approach is touched upon by the Buddhist Mahasiddha Saraha who in once sang:

This is the River Yamuna,

This is the River Ganga,

Varanasi and Prayaga,

This is the moon and the sun.

Some speak of realization having traveled and seen all lands,

The major and minor places of pilgrimage.

Yet even in dreams I have no vision [of these].

There is no other boundary region like the body;

I, virtuous, have seen this for good and with certainty.

Stay in the mountain hermitage and practice self-restraint.[i]

In his book Sacred Ground, Ngawang Zangpo has addressed in a very detailed manner the thoughts of Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Thaye on the importance of sacred geography. Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Thaye lived in Tibet from 1813 to 1899. He was a famous meditation master of the Kagyu, the Nyingma and Sakya Lineages. Through his wide and open attitude Kongtrul helped define and spread the Rime, or non-sectarian view of the dharma, in response to a general atmosphere of sectarianism amongst all schools of Buddhism in Tibet at the time. He was a compiler of termas (revealed treasure teachings) and was a terton (treasure discoverer) in his own right. A real renaissance man, Kongtrul not only helped shape and preserve the Kagyu lineage, but all forms of Dharma in Tibet.

Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Thaye identified a variety of places in Tibet as reflections of the twenty-four pithas in India. This change in perspective had the effect of being quite dynamic in that it placed Tibetans directly in the center of their own world of sacred geography. Of course some brave souls still made the journey to the twenty-four pithas in India, but many visited the sites that Kongtrul and his dharma friends Chokgyur Dechen Lingpa and Jamyang Kheyntse Wongpo felt were equivalent. For some, this type of translation/re-orientation was too much; indeed the great Sakya patriarch Sakya Pandita took issue with the possibility that several pithas could be located in Tibet.

Sacred Ground is an excellent book for exploring the thoughts and teachings of Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Thaye on the subject of pilgrimage and inner spiritual geography. Ngawang Zangpo translates Kongtrul Rinpoche’s Pilgrimage Guide to Tsadra Rinchen Drak [or Pilgrimage Guide to Jewel Cliff that resembles Charitra (the union of everything)]- an amazing text that treats in great depth the nature of that particular pilgrimage location as well as it’s inner and secret significances as it relates to various energetic centers found throughout the body. Zangpo includes a chart listing the manner in which the pithas correspond to the body according to the Chakrasamvara tantra, an appendix that includes three fascinating texts one by Kongtrul and Khyentse Wongpo, one by Chokgyur Lingpa, and a compiled list of sacred sites in Tibet by Ngawang Zangpo. Of particular interest is a reference to a note found in Mattheiu Ricard’s translation of The Life of Shabkar:

It must be remembered that sacred geography does not follow the same criteria as ordinary geography. Kyabje Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche (1910-91), for instance, said that within any single valley one can identify the entire set of the twenty-four sacred places. Kyabje Dudjom Rinpoche (1903-87) also said that sacred places, such as Uddiyana, can shrink and even disappear when conditions are no longer conducive to spiritual practice. The twenty-four sacred places are also present in the innate vajrabody of each being. (p.442, n.1)

A similarly fascinating book on this subject is the collection of essays edited by Toni Huber entitled Sacred Spaces and Powerful Places in Tibetan Culture. These essays offer a rich exploration of issues surrounding pilgrimage sites, sacred geography and geomancy. Of particular interest is the essay by David Templeman entitled Internal and External Geography in Spiritual Biography in which he explores the relationship that the mahasiddha Krishnacharya with the twenty-four pithas, especially that of Devikotta. Templeman considers the importance of these sites as internal locii and suggests that while pilgrimage to these sites was indeed important, there is little evidence to support that many siddhas visited all of them. In fact, Templeman suggests that some sites more than others are of particular significance and have been over time, while others are dangerous, home to subtle harmful beings (wild flesh eating dakinis) that need to be appropriately tamed before one can occupy that particular location. In the case of the mahasiddha Krishnacharya, his untimely end occurred at the site of Devikotta, as this site had a reputation for incredible unpredictable volatility that was well known throughout India at the time.

I tend to wonder where this place of volatility, with beings that need to be subjugated, resides within me. A three paneled chart provided by Templeman in his article listing the twenty-four pithas according to the Chakrasamvara Tantra, the teacher Jonang Taranatha and the Sakya master Kunga Drolchok, indicates that Devikotta -this very powerful site- is located within my energetic body around both of my eyes. I wonder where it’s mirror locations are?

What I find most compelling about these books, and this subject in general is that it has a lot to do with how we relate to the world around us, how we import meaning to this world, and what we allow of ourselves in being in relation to time and space. The essays in Huber’s book and the work by Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Thaye describe both the Tibetan cultural, as well as the general vajrayana approach to sacred geography- these two are not by all means identical as Huber points out in his essay. Huber suggests that Tibetan culture influenced vajrayana making it distinct from the Tantric Buddhism that developed in India which then spread to Tibet. While the distinction is subtle, it speaks to how meaning is translated. It is arguable that there can never be a one-for-one translation of a text from one language to another, and perhaps, a one-to-one translation of a religion is similarly unlikely. That said, without straying into the soft edges of hermeneutics, I would like to wonder out loud, “How does Buddhist sacred geography translate to Buddhism in the ‘West’?” I think that a great response to such a question is, “That’s a silly question, Buddhist sacred geography is as present in the west as it is in Tibet or India”. I’d also add that we should map it, live within it in a more open way, and make it ours.

If Jalandhara is a site that corresponds to the crown of my head, Oddiyana a site that corresponds to my right ear, and Devikotta my two eyes, all the while representing sacred places reflected upon the Indian Sub-continent and or the Tibetan Plateau, where would they be reflected upon the geography of the United States for example? Or more playfully perhaps, Brooklyn? It seems that some of this has to do with fully owning and bringing vajrayana home. In so doing, I would love to see how this type of re-orientation occurs. Can we do for ourselves what Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Thaye did for Tibetans?

As Buddhism takes root here in the U.S. and continues to flourish I would love to see all of the twenty-four pithas of the India subcontinent reflected here. Perhaps as we learn to slow down and notice our relationship with our surroundings this will be more evident. I’m very curious to see how this aspect of vajrayana in particular translates to western culture; it seems like there is great potential.

[i] Schaeffer, Kurtis R. Dreaming the Great Brahmin: Tibetan Traditions of the Buddhist Poet-Saint Saraha. Oxford University Press, 2005. Pg. 151.

![Validate my RSS feed [Valid RSS]](valid-rss-rogers.png)