on pacifying, enriching, magnetizing and subjugating…

I recently attended a long weekend retreat on the Five Remembrances held by the New York Zen Center for Contemplative Care. It was wonderful to have time at the Garrison Institute to reflect upon these five essential points:

I am of the nature to experience old age, I cannot escape old age.

I am of the nature to experience illness, I cannot escape illness.

I am of the nature to experience death, I cannot escape death.

I am of the nature to experience loss of all that is dear to me, I cannot escape loss.

I am the owner of my actions. They are the ground of my being, whatever actions I perform, for good or ill, I will become their heir.

The Five Remembrances come from the Upajjhatthana Sutra which could be translated as The Sutra of Subjects of Contemplation. You can hear the teaching of the Five remembrances as found in the Upajjhatthana Sutta read by Kamala Masters here, or read a portion of the sutta translated by Thanissaro Bhikkhu here.

The Buddha’s discourse on the Five Remembrances resembles the realization that young Prince Siddhartha had concerning his recognition that we are all subject to birth, sickness, old age, death, and all of the forms of suffering associated with each phase of our existence. In the reading of the sutta by Kamala Masters, the Buddha points out that the first four Remembrances serve us well to return our focus onto the primacy of impermanence; doing so is a remedy towards arrogance, over-confidence, and conceit.

I will become sick. I will become old. I will experience loss. I will die. There is nothing that I can do to change this. When that happens, as this whole existence plays out, my only companion who remains with me throughout is the collection of my actions.

The Fifth Remembrance, which relates to our actions, the quality of our actions, or karma, colors the experience of each facet of our being. It can be the root of our liberation, or the hard kernel from which our suffering manifests. I’d like to take a moment to explore the Fifth remembrance, our actions, in a general sense and then look a little more specifically at action from the Vajrayana buddhist perspective, especially as it relates to actions of pacifying, enriching, magnetizing and subjugating.

Action, movement, friction, trajectories, potential energies. These can easily refer to different forces and dynamics involved within the study of physics, which at close glance looks like a wonderful symbolic structure parallel to aspects of Buddhism, and yet as qualities they easily also connect to our behavior. Our behavior is composed of reactions or responses to the events around us, how we see the play of phenomena unfold before our very eyes. The quality of our perspective acts to determine the flavor of our actions, and the quality of our actions affects the continuum of our perspective. The more self-involved our perspective is, the more our actions involve the preservation and protection of self interests. The more we act to preserve and protect self-interests, the more easily we may think that others or events may be hindering our self-interests. Likewise, a more expansive perspective affords us the ability to act in a more expansive way. When we act with a larger concern for others’ well being, our ability to see the interrelatedness of self and other allows more clarity and more peace.

As we pass through this life, a conditioned existence that has been flavored by past events, the habits of reacting to the display of phenomena around us (our daily lives) often become stronger and more ridgid. The phrase goes: Actions speak louder than words. This seems right, but it’s amazing how we use thousands of words to hide or cover up and beautify our actions. Such elaborate verbal adornments so that we can feel okay about how we are right now.

The above image is that of Senge Dradrok, or Lion’s Roar, one of the eight manifestations of Guru Rinpoche. Guru Rinpoche took this form in Bodh Gaya when he came to debate and challenge a group of five hundred non-Buddhist teachers who were trying to disprove the Buddha’s teachings. Guru Rinpoche won the debate and “liberated” all of them with a bolt of lightening- most of the village where the non-buddhists were staying was destroyed, those who survived became converts to Buddhism. This type of story is not so unique. The life story of the Mahasiddha Virupa and many others contain descriptions of such events- they are powerful descriptions of activities that certainly appear to run counter to the typical notion of what buddhist behavior is thought to be. This energy of wrathful subjugation, while not generally an everyday occurrence has it’s place- this hot humid searing energy is needed from time to time to remove impediments towards our spiritual growth.

How can we touch the quality of Senge Dradrok within ourselves? What does it feel like to be him, or Mahakala, Vajrakilya, or Palden Lhamo? What is the focus of these energies? How can we completely liberate the hundreds on non-dharmic impulses within us like Senge Dradrok?

In another form, that of Nyima Ozer, or Radiant Sun, Guru Rinpoche displayed himself as Saraha, Dombi Heruka, Virupa, and Krishnacharya, some of the most well-known Indian proponents of tantric Buddhism. While in this form Guru Rinpoche spent time in the eight great charnel grounds and taught Secret Mantra (tantric Buddhism) to the dakinis, while binding outer gods as protectors of his secret teachings. This is an act of magnetizing, drawing towards him the dakinis and protectors of his treasured teachings, spreading the dharma in the form of may important masters. In the form of a tantric master his intensity and use of whatever arises as a teaching tool captures the great energy deeply-seated within through which magnetizing activity becomes manifest. It seems that essential to the quality of magnetizing is the general awareness of skillful means; knowing just when to act in a way to be of the most benefit in any given situation.

Yet another activity form of Guru Rinpoche appears as Pema Gyalpo, or Lotus King. In the form of Pema Gyalpo, Guru Rinpoche taught the inhabitants Oddiyana the Dharma as he manifested as the chief spiritual advisor for the King of Oddiyana. His selfless dedication and compassionate timely teaching activity enriched all who came into contact with Pema Gyalpo such that they became awareness-holders in their own right. This enriching activity has untold benefits; the effects of the nurturing support that Pema Gyalpo displayed through his teaching activity caused an incredible expansion of the Dharma in Oddiyana.

This final image is of Guru Rinpoche as himself, who among most Himalayan Buddhists is considered the second Buddha in the sense that he is credited with bringing Buddhism to Tibet. While he wasn’t technically the first, he was the first to introduce tantric Buddhism in a way that took hold, and is credited with helping to construct the first Buddhist monastery in Tibet. A dynamic teacher, Guru Rinpoche embodied all of the qualities of his eight manifestations and countless others. Through the expression of his life Guru Rinpoche was able to display pacification, enriching, magnetizing, and subjugation both in Oddiyana, India, Bhutan, Tibet, and even now.

Within tantric Buddhist literature we often find references to the importance of adopting the behavioral modalities of pacifying, enriching, magnetizing, and subjugating as illustrated by the eight manifestations of Guru Rinpoche. These activities were seen as extremely important as they pertain to embodying the qualities of a variety of tantric buddhas as well as the essence of Buddhahood in all emotions. Furthermore, they are utilitarian activities, they support and enrich and massage us as we travel the path of enlightenment. References to these activities can be found in the translations of various tantric texts by a variety of outstanding Buddhist scholars such as David Snellgrove, David B. Gray, Christian K. Wedemeyer, and Vesna A. Wallace to name a few. One can also rely upon the namthars (liberation stories) of many Indian and Himalayan Buddhist Siddhas to feel the range of possible human action on both inner and outer levels of being. Finally, our practice sadhanas contain a wealth of wisdom and guidance- the words in sadhanas are not arbitrary- and they often capture with great clarity the essence of dharma being.

We are aging. We will experience illness. We will die. We will experience loss. Our actions are our ground and we are the owners of our actions. That this is the case is undeniable. We cannot change the first five certainties, but we can change our actions. Our actions, and the related ability to perceive, directly determine how we relate qualitatively towards aging, illness, death, and impermanence. Let’s apply the depth and range of possibilities as exemplified by Guru Rinpoche and other Buddhist Siddhas- lets refine, strengthen, expand, and deepen our relationships with ourselves, with the world around us and with our experience of mind. We are completely capable of manifesting in this way- it doesn’t matter if we wish to embody Tilopa, Virupa, Tsongkhapa, Taranatha, Machik Labron, or Garab Dorje, we are all capable of touching their essential being. No one can do this for us. At the end, as we lay dying, who can really blame for our shortcomings?

Sacred geography: external, internal and in-between

As part of my CPE (Clinical Pastoral Education) training with the New York Zen Center for Contemplative Care we have been exploring aspects of Jungian psychology especially as it relates to symbols and images. We recently finished a great week of classroom experience which included a conversation with Morgan Stebbins, the Director of Training of the Jungian Psychoanalytic Association, a faculty member of the C.G. Jung Foundation of New York, and a long time student of Buddhism. Stebbins’ presentation on Symbol and Image was dynamic and quite moving- he embodies a depth and conviction that I find compelling. In addition to this, Stebbin’s visit to our class came at a point when I’ve been playing around with writing a blog post about sacred geography. Very timely indeed.

As part of my CPE (Clinical Pastoral Education) training with the New York Zen Center for Contemplative Care we have been exploring aspects of Jungian psychology especially as it relates to symbols and images. We recently finished a great week of classroom experience which included a conversation with Morgan Stebbins, the Director of Training of the Jungian Psychoanalytic Association, a faculty member of the C.G. Jung Foundation of New York, and a long time student of Buddhism. Stebbins’ presentation on Symbol and Image was dynamic and quite moving- he embodies a depth and conviction that I find compelling. In addition to this, Stebbin’s visit to our class came at a point when I’ve been playing around with writing a blog post about sacred geography. Very timely indeed.

“What does sacred geography have to do with me?” one might ask. I would answer, “Everything”.

Within the framework of Buddhism geography and therefore pilgrimage, has come to be something of an important phenomena. Certainly this is not anything unique to Buddhism; we have a tendency to want to return to places that are significant for us. Sometimes there is spiritual significance, sometimes it is societal, and most often it is interpersonal. An example of these would be making the Hajj if you were Muslim, perhaps visiting Washington D.C., or taking your children there so that they could appreciate the way that our nation governs itself, and perhaps the place where one’s parents were born, or where they died. Geography allows us to honor the meaning that we value in our lives. We live within time and space, and within the latitude and longitude that time and space afford us, we intentionally (and even unintentionally) plot the course of our lives and identities within their dynamics. How many times has a particular season or even date reminded us of an event that occurred in the past around the same time? My root teacher passed away on Christmas eve over a decade ago, and I am always reminded of that great loss whenever Christmas approaches. On the other hand, the Fall months feel like a time of rich growth for me- they always have, and for some reason these months continue to prove to be significant for me. These are two examples of how I plot meaning within my experience of time.

In most faiths pilgrimage has become something that one engages to touch the past; it is a means to feel the link of those who have come before us and charge the present moment with their power. It can be the Wailing Wall, St. Peters, the Kabba, Bodh Gaya, a sacred mountain, river, the ocean, a tree and it can also be imagined- something symbolic, a living pulsating image such as a mandala.

According to the Mahaparinirvana Sutra, the Buddha predicted that students of the path would visit the place of his birth, his enlightenment, where he first taught, and where he would die. He stressed that this may be something that one does if they want to, if it brings meaning, inspiration, and context to their path. It was a suggestion, not a directive, and ultimately a very insightful reading of how we relate to time and space.

Within Vajrayana, or tantric Buddhism, pilgrimage appears in a more visionary manner. In addition to the four major sites associated with the Buddha’s life, various pithas, or ‘seats’ (places of power and meaning associated with the dissemination of Buddhist tantra) became included into various lists of sacred places. For example, there are twenty-four pithas throughout the Indian sub-continent that are associated with the places where the Buddha revealed himself as Chakrasamvara and taught the cycle of Chakrasamvara and related practices. The pithas, while relating to actual places, also correspond to places within our bodies that have an internal energetic significance. The exact location of these pithas vary from tradition to tradition, but there is a relative constancy of the mirroring of external and internal meaning in relation to these sites. In some ways, and according to some teachers, pilgrimage can be done without ever leaving where you are as all of the major pithas exist within the matrix of our energetic body. This approach is touched upon by the Buddhist Mahasiddha Saraha who in once sang:

This is the River Yamuna,

This is the River Ganga,

Varanasi and Prayaga,

This is the moon and the sun.

Some speak of realization having traveled and seen all lands,

The major and minor places of pilgrimage.

Yet even in dreams I have no vision [of these].

There is no other boundary region like the body;

I, virtuous, have seen this for good and with certainty.

Stay in the mountain hermitage and practice self-restraint.[i]

In his book Sacred Ground, Ngawang Zangpo has addressed in a very detailed manner the thoughts of Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Thaye on the importance of sacred geography. Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Thaye lived in Tibet from 1813 to 1899. He was a famous meditation master of the Kagyu, the Nyingma and Sakya Lineages. Through his wide and open attitude Kongtrul helped define and spread the Rime, or non-sectarian view of the dharma, in response to a general atmosphere of sectarianism amongst all schools of Buddhism in Tibet at the time. He was a compiler of termas (revealed treasure teachings) and was a terton (treasure discoverer) in his own right. A real renaissance man, Kongtrul not only helped shape and preserve the Kagyu lineage, but all forms of Dharma in Tibet.

Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Thaye identified a variety of places in Tibet as reflections of the twenty-four pithas in India. This change in perspective had the effect of being quite dynamic in that it placed Tibetans directly in the center of their own world of sacred geography. Of course some brave souls still made the journey to the twenty-four pithas in India, but many visited the sites that Kongtrul and his dharma friends Chokgyur Dechen Lingpa and Jamyang Kheyntse Wongpo felt were equivalent. For some, this type of translation/re-orientation was too much; indeed the great Sakya patriarch Sakya Pandita took issue with the possibility that several pithas could be located in Tibet.

Sacred Ground is an excellent book for exploring the thoughts and teachings of Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Thaye on the subject of pilgrimage and inner spiritual geography. Ngawang Zangpo translates Kongtrul Rinpoche’s Pilgrimage Guide to Tsadra Rinchen Drak [or Pilgrimage Guide to Jewel Cliff that resembles Charitra (the union of everything)]- an amazing text that treats in great depth the nature of that particular pilgrimage location as well as it’s inner and secret significances as it relates to various energetic centers found throughout the body. Zangpo includes a chart listing the manner in which the pithas correspond to the body according to the Chakrasamvara tantra, an appendix that includes three fascinating texts one by Kongtrul and Khyentse Wongpo, one by Chokgyur Lingpa, and a compiled list of sacred sites in Tibet by Ngawang Zangpo. Of particular interest is a reference to a note found in Mattheiu Ricard’s translation of The Life of Shabkar:

It must be remembered that sacred geography does not follow the same criteria as ordinary geography. Kyabje Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche (1910-91), for instance, said that within any single valley one can identify the entire set of the twenty-four sacred places. Kyabje Dudjom Rinpoche (1903-87) also said that sacred places, such as Uddiyana, can shrink and even disappear when conditions are no longer conducive to spiritual practice. The twenty-four sacred places are also present in the innate vajrabody of each being. (p.442, n.1)

A similarly fascinating book on this subject is the collection of essays edited by Toni Huber entitled Sacred Spaces and Powerful Places in Tibetan Culture. These essays offer a rich exploration of issues surrounding pilgrimage sites, sacred geography and geomancy. Of particular interest is the essay by David Templeman entitled Internal and External Geography in Spiritual Biography in which he explores the relationship that the mahasiddha Krishnacharya with the twenty-four pithas, especially that of Devikotta. Templeman considers the importance of these sites as internal locii and suggests that while pilgrimage to these sites was indeed important, there is little evidence to support that many siddhas visited all of them. In fact, Templeman suggests that some sites more than others are of particular significance and have been over time, while others are dangerous, home to subtle harmful beings (wild flesh eating dakinis) that need to be appropriately tamed before one can occupy that particular location. In the case of the mahasiddha Krishnacharya, his untimely end occurred at the site of Devikotta, as this site had a reputation for incredible unpredictable volatility that was well known throughout India at the time.

I tend to wonder where this place of volatility, with beings that need to be subjugated, resides within me. A three paneled chart provided by Templeman in his article listing the twenty-four pithas according to the Chakrasamvara Tantra, the teacher Jonang Taranatha and the Sakya master Kunga Drolchok, indicates that Devikotta -this very powerful site- is located within my energetic body around both of my eyes. I wonder where it’s mirror locations are?

What I find most compelling about these books, and this subject in general is that it has a lot to do with how we relate to the world around us, how we import meaning to this world, and what we allow of ourselves in being in relation to time and space. The essays in Huber’s book and the work by Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Thaye describe both the Tibetan cultural, as well as the general vajrayana approach to sacred geography- these two are not by all means identical as Huber points out in his essay. Huber suggests that Tibetan culture influenced vajrayana making it distinct from the Tantric Buddhism that developed in India which then spread to Tibet. While the distinction is subtle, it speaks to how meaning is translated. It is arguable that there can never be a one-for-one translation of a text from one language to another, and perhaps, a one-to-one translation of a religion is similarly unlikely. That said, without straying into the soft edges of hermeneutics, I would like to wonder out loud, “How does Buddhist sacred geography translate to Buddhism in the ‘West’?” I think that a great response to such a question is, “That’s a silly question, Buddhist sacred geography is as present in the west as it is in Tibet or India”. I’d also add that we should map it, live within it in a more open way, and make it ours.

If Jalandhara is a site that corresponds to the crown of my head, Oddiyana a site that corresponds to my right ear, and Devikotta my two eyes, all the while representing sacred places reflected upon the Indian Sub-continent and or the Tibetan Plateau, where would they be reflected upon the geography of the United States for example? Or more playfully perhaps, Brooklyn? It seems that some of this has to do with fully owning and bringing vajrayana home. In so doing, I would love to see how this type of re-orientation occurs. Can we do for ourselves what Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Thaye did for Tibetans?

As Buddhism takes root here in the U.S. and continues to flourish I would love to see all of the twenty-four pithas of the India subcontinent reflected here. Perhaps as we learn to slow down and notice our relationship with our surroundings this will be more evident. I’m very curious to see how this aspect of vajrayana in particular translates to western culture; it seems like there is great potential.

[i] Schaeffer, Kurtis R. Dreaming the Great Brahmin: Tibetan Traditions of the Buddhist Poet-Saint Saraha. Oxford University Press, 2005. Pg. 151.

His Holiness Karmapa on the Kagyu Monlam

Composed by His Holiness the Seventeenth Karmapa, Ogyen Trinley Dorje

like nectar flowing from a spring on a snowy mountain face,

from some highest of realms high above,

with effortless vigor and a deep, unprompted longing,

drop after divine drop, each pristine and pure,

you crossed the mountains and plains of hundreds of months and years,

to come cascading down, down into the land of our hopes.

coursing through deep aspirations you held, held through the stream of many lives,

from some place completely obscured to us, you gave gentle warmth and nourished us.

since then, the tender young sprouts of virtuous minds

have blossomed with leaves and fruit,

and land once scorched with drought burst into life turquoise-green.

when a snow lion roars on a white mountain peak

the sound at once sends the crisp flakes swirling in a flurry.

when you arrived in the year eleven-ten

the lion’s roar of your majestic name blazed forth,

spreading its unchanging splendor and unequalled blessings.

day and night, for nine hundred years,

it has set trembling the hearts of those with faith, scared away the sleep of our ignorance

and stilled the waves of thought that trouble the ocean of our minds.

with the fearful crash of its sound, the haughty become hushed and still.

because you are here, we dare to face the angry countenance of the samsaric sea.

because you are here, we know that there is an end to this suffering.

the world, its voice raised in cries of birth and death, falls silent.

your deeds blend completely with a sky as deep blue as your brilliant crown.

your great heart, like a splendid mandala of wind,

keeps this world ever moved.

O Karmapa, you who act,

I am all that you have. and you are all that I have.

A feast song by the 3rd Karmapa Rangjung Dorje

As the Kagyu monlam begins I would like to share a feast song, a ganachakra celebration, composed by the third Karmapa Rangjung Dorje.

With the monlam and all of its blessings in mind, I offer this song. May the Kagyu monlam benefit all beings, and may the activities of His Holiness the 17th Karmapa Orgyen Trinley Dorje be vast!

A Feast Song in Lhasa

I salute the guru Jewel.

In the ocean of true essence

arise multitudes of unreal concepts,

like varied patterns in the water.

Therefore I practice the following.

This heroic feast- the culmination of merit

for the profound mother tantra-

was taught to increase the merit of beings.

Thus do I understand its meaning:

Beings of the beginning stage

should visualize their body as a deity

at this stage of imaginative engagement.

Purify food and drink into nectar,

and offer the skandhas to the victorious sages.

This is called the great feast:

heros and heroines equal in number,

who have attained high realizations,

contemplate the essence of void and bliss

amid the abundance of food and drink.

Great is the assembly at the feast!

Since all heros have gathered,

it is called the joyous feast of heros.

The Master knows the way of mantra,

his mindstream is empowered,

he understands the essential precepts;

disciple-hosts of heroines and heros,

together engage in full absorption-

the stages of generation and completion-

immeasurable are the attainments of the feast.

Those who do not possess such virtues,

and wrongly take out of self-importance,

will encounter obstacles; this is foretold.

Though I have not seen the assembled heros,

I have sung the essence of the tantric scriptures;

for this is called the essential instruction.

Be inspired with wondrous admiration.

Join the celebration, partake fully in the feast!

(This poem was sung in Lhasa at the assembly gathered to celebrate a religious feast on the evening of the eighth day of the tenth month of the dragon year)[i]

[i] Taken from Songs of Spiritual Experience, trans. By Thupten Jinpa and Jas Elsner. Shambala, 2000.

Kalu Rinpoche and Bokar Rinpoche, Father and Son, protectors of the Kagyu Monlam.

It has always felt to me that if Kyabje Kalu Rinpoche was the essence of Milarepa, then Kaybje Bokar Rinpoche was the essence of Gampopa. While I never had the chance to meet Kalu Rinpoche, I have met many Tibetan, American, British and French students of Rinpoche who often spoke of his direct orientation towards practice, his passion for transmitting instruction, and his easy going trust in the dharma- these seem to be qualities that I associate with Milarepa.

Similarly, Bokar Rinpoche with his purity of heart, emphasis upon transmission of the lineage teachings and stainless vinaya, truly does remind me of qualities that were emblematic of Je Gampopa. In expressing the direct simplicity of mind, Kyabje Bokar Rinpoche was known as a great master of Mahamudra.

That they both maintained, preserved and expanded the Kagyu Monlam in Bodh Gaya is important. Kyabje Kalu Rinpoche can be credited with establishing the Kagyu monlam in Bodh Gaya. When he began the monlam it was a small informal gathering. After his passing, Kyabje Bokar Rinpoche continued the practice of maintaining and further developing the Kagyu monlam; it slowly grew and grew. I attended several of these earlier monlams where Bokar Rinpoche and Yangsi Kalu Rinpoche presided over a much smaller number of monks, nuns and lamas than those that attend present monlam celebrations. They were a combination of grand and intimate, which seemed just right for reciting aspiration prayers and receiving inspiration.

After His Holiness the 17th Karmapa escaped from Tibet in January of 2000 and was allowed to travel inside of India, he presided over the monlam. Its as if Kyabje Kalu Rinpoche and Kyabje Bokar Rinpoche were keeping his Holiness’ seat warm under the bodhi tree. Since the sudden death of Kyabje Bokar Rinpoche, the monlam has been run by Lama Chodrak (the lama he appointed to organize the monlam) and the monlam committee. His Holiness the 17th Karmapa has also taken a strong role in monlam planing, and feels strongly about its mission and goals.

With their activities in mind I offer this song of supplication written by Kaybje Bokar Rinpoche. May it be of benefit!!

Wide Wings That Lift Us to Devotion: A supplication

A Vajra song by Kyabje Bokar Rinpoche

Spiritual master, think of me! Think of me!

Source of all blessings, root spiritual master, think of me!

Spiritual Master, think of me! Think of me!

Epitome of all accomplishment, root spiritual master, think of me!

Spiritual master, think of me! Think of me!

Agent of all enlightened activity, root spiritual master, think of me!

Spiritual master, think of me! Think of me!

All refuges in one, root spiritual master, think of me!

Turn all beings’ minds, with mine, towards the Teachings.

Bless me that all stages of the faultless path-

Renunciation, the mind of awakening, and the correct view-

Genuinely arise in my being.

May I dwell untouched by the faults of pride and wrong views

Toward the Teachings and the teacher of freedom’s sublime path.

May steadfast faith, devotion and pure vision

Lead me to fully achieve the two goals for others and myself.

The Human tantric master introduces my intrinsic essence.

The master in the Joyful Buddha’s Canon instills certainty.

The symbolic master in appearances enriches experience.

The ultimate master, the nature of reality, sparks realization of the abiding nature.

Finally, within the state of the master inseparable from my own mind,

All phenomena of existence and transcendence dissolve into the nature of reality’s expanse;

The one who affirmed, denied and clung to things as real vanishes into the absolute expanse-

May I then fully realize the effortless body of ultimate enlightenment!

In all my lifetimes, may I never be separate from the true spiritual master.

May I enjoy the Teachings’ glorious wealth,

Completely achieve the paths and stages’ noble qualities,

And swiftly reach the state of Buddha Vajra Bearer.

In 1995, in response to requests from two translators, Lama Tcheucky and Lama Namgyal, on behalf of my foreign disciples, I, Karma Ngedon Chokyi Lodro, who holds the title of Bokar Tulku, wrote this at my home in Mirik Monastery. May it prove meaningful.[i]

[i] Zangpo, Ngawang. trans. Timeless Rapture: Inspired Verse of the Shangpa Masters. Snow Lion Publications. 2003. Ithaca, NY., Pg. 215-217.

his holiness the 16th karmapa on the nature of mind

In honor of the approaching 28th annual Kagyu monlam in Bodh Gaya I would like to share a pith instruction of His Holiness the 19th Karmapa Rangjung Rikpai Dorje. While every year is special, and every Kagyu monlam is truly a wonderous event, this year’s monlam coincides with the 900 year anniversary of the birth of the first Karmapa, Dusum Khyenpa. This is a moment to celebrate and praise the history of the Kamstang Kagyu Lineage and all of its wonderous lineage holders, siddhas, yogins and yoginis. Emaho! I am humbled to know that His Holiness the 17th Karmapa, Orgyen Drodul Trinley Dorje will be leading the prayers along with the leading lineage holders of the Kagyu lineage.

You can learn more about this year’s monlam, its schedule and special activities here.

His Holiness the 16th Karmapa on pointing out the nature of mind

Here, in the thick darkness of deluded ignorance,

There shines a vajra chain of awareness, self-arisen with whatever appears.

Within uncontrived vividness, unimpeded through the three times,

May we arrive at the capital of nondual, great bliss.

Think of me, think of me; guru dharmakaya think of me.

In the center of the budding flower in my heart

Glows the self-light of dharmakaya, free of transference and change,

that I have never been separate from.

This is the unfabricated wisdom of clarity-emptiness, the three kayas free of discursiveness.

This is the true heart, the essence, of the dharmakaya, equality.

Through relying on the display of the unfabricated, unceasing, unborn, self-radiance,

May we arrive at the far shore of samsara and nirvana- the great, spontaneous presence.

May we enter the forest of the three solitudes, the capital of the forebears of the practice lineage.

May we seize the fortress of golden rosary of the Kagyu.

O what pleasure, what joy my vajra siblings!

Let us make offerings to dharmakaya, the great equal taste.

Let us go to the great dharmadhatu, alpha purity free from fixation.

They have thoroughly pacified the ocean of millions of thoughts.

They do not move from the extreme-free ocean of basic space.

They posses the forms that perfect all the pure realms into one-

May the auspiciousness of the ocean of the protectors of being be present.

In the second month of the Wood Hare year (1976), [His Holiness] spoke these verses at Rumtek Monastery, the seat of the Karmapa, during the ground breaking ceremony for the construction of the Dharmachakra Center for Practice and Study.

purity, impurity and inner offerings

From the nature of emptiness wind and fire arise.

I remember very clearly the cold late November afternoon in Gangtok, Sikkim, fifteen years ago when I was taught Milarepa guru yoga. It was one of those incredible experience of being shown something for the first time: electrifying, new and magical. One of the things that instantly spoke to me about the practice was the imagery of the inner offering of the five meats and five nectars that appears in the beginning of the text. Indeed, in looking back at it I think that the inner offering in Milarepa practice (as well as in many other tantric Buddhist practices) has been something that has held great meaning for me. Part of it may be the fact that this prelude to Milarepa practice is a wonderfully clear metaphor for Mahamudra; one of the central forms of meditation passed down through the Kagyu Lineage. The inner offering presents a different form for approaching the mind’s essence from other meditations- chod involves cutting and offering, samatha/vipassana is quiet and still, some practices involve fiery wrath, others still, a warm familiar tenderness. Each of these emotive backgrounds illustrate a modality, an emotion, a style, or an outlet through which we may we express and experience ourselves within the context of awakened activity; the union of clarity of being and luminosity of mind. Within the context of the inner offering, the metaphor is that of boiling and melting (not unlike the athanor which refines the prima materia in Alchemy). This burning and melting is so powerful that a sublime blissful nectar is produced, a non-dual nectar that confers the blessing of the Buddha. This part of Milarepa guru yoga came to be, and remains, an exciting fun part of my practice, instilling a sense of dynamic power that seems to illustrate the potential “atomic” nature of Vajrayana.

In a skull on a tripod of skulls GO KU DA HA NA become the five meats and BI MU MA RA SHU become the five nectars.

The inner offering is a product of medieval India (roughly between the 6th through 12th centuries), when both Tantric Buddhism and Tantric Hinduism were taking shape. This was a time of immense social upheaval throughout the Indian sub-continent. In both Hindu and Buddhist circles, groups of siddhas broke away from the orthodoxy of their respective majorities in order to develop, practice and teach tantric forms of Hinduism and Buddhism. One of the principal causes of such a move was a the adoption of an antinomian attitude towards the strictures of Indian society with its caste system, its brahmanic tendencies towards “purity”, and the establishment of Buddhist monasteries so large and wealthy that their leading teachers often lived very comfortable lives of scholastic celebrity. This shift was often exemplified by the lives of the 84 mahasiddhas, some of whom left their teaching positions at the famous monasteries of Nalanda, Somapuri, and Vikramashila to practice in jungles, others were kicked out for their outlandish behavior, while a few were kings or princes and princesses afraid to give up their wealth, and many were of low-caste status. Disregard for the religious and cultural status quo led to a shift towards the charnel grounds as gathering places, frightening “dirty” locations, where wild animals scavenged the remains of the recently dead. It was a time where meditation instruction was sung in vernacular so that the everyday person could be touched, not just those who were ordained or occupants of a higher social station. This time also marked a focal shift (as far as practice goes) towards cities where the concentrated hustle and bustle of everyday life revealed itself as a ripe field of opportunity, a place where one is faced to deal with a full range of emotions. For some it was also a shift into the seductive luxurious courts of both major and minor royalty. Human experience, in all of its forms was recognized as embryonic in nature allowing most anyone who exerted themselves in practice to become pregnant with realization. This became the birth right of all, not just those born into one caste, and certainly not just those who were literate or educated. Perhaps one could go so far as to say that this period was a time of spiritual anarchic-democratization.

One of the most interesting aspects of this time period was the apparent looseness of sectarian divisions between the then Saivite sub-sects that represented the forefront of Hindu tantra and the Buddhist equivalents who ushered in Chakrasamvara, Hevajra, Candamaharosana, Guhyasamaya and other early tantric deity practice. The shared iconography between Saivite Kapalika Hindu tantra and Buddhist tantra is clear evidence of some common direction and praxis orientations. Such symbolism makes use of skulls, flayed animal and human skins, invocations of the more wrathful nature of these deities, and sexual union with their consorts. Similarly, the dual identities of the siddhas Matsendryanath, Gorakanath, Jalandhara, and Kanhapa who are counted as four of the eighty-four Buddhist mahasiddhas as well as founders of the Hindu Nath lineages suggests that there was much more dialog between the more iconoclastic progenitors and practitioners of Hindu and Buddhist Tantra. These four siddhas are credited with the development of Hatha Yoga, which has many applications within Buddhism and Hinduism. David Templeman, in his fascinating paper Buddhaguptanatha and the Survival of the Late Siddha Tradition has suggested that the interaction between Buddhist and Hindu yogins was more common than most Tibetan scholars had assumed. This was a perplexing and fascinating subject for the erudite Tibetan scholar Taranatha, and according to Janet Gyatso, in her book Apparitions of the Self, the great Nyingma terton Jigme Lingpa was very curious about such points of contact. In some way it appears that the assumption of difference seems to be a convenient projected organizational tool used to try to clarify such a difficult topic of study. A way to try to define that which tries to defy definition. The Centre for Tantric Studies offers a forum for exploring the history and development of tantra in and around the Indian Sub-continent.

Much debate and uncertainty surrounds the issue of how tantra came into being, even more debate surrounds how we should approach understanding tantra. The works of scholars like Geoffrey Samuel, Roger Jackson, Ronald Davidson, David Gordon White, Elizabeth English and Christian Wedemeyer (to name a few) have helped to illustrate some of the more pertinent issues surrounding the subject of Buddhist tantra.

They are melted by wind and fire.

As a means of throwing open the gates of ultimate realization, the Pancamakara: madya (alcohol), mamsa (meat), matsya (fish), mudra (edible foods) and maithuna (sexual intercourse) were included in Hindu tantric rituals as a means to effect a eucharistic understanding of non-duality. In essence, by consuming that which is culturally regarded as impure in ritual context, one undermines the very notion of the purity/impurity dualism that keeps us trapped in feeling fragmented and lacking expansiveness. These particular objects, when handled and offered by practitioners of this more radical form of Hindu Tantra were held with the left hand, the hand reserved for handling impure substances. In adopting an enthusiasm and greater equanimity towards these violations of cultural mores regarding cleanliness (spiritually as well as otherwise) one was directly contradicting the rules of conventional Hinduism. It should be noted that the use of the left hand in offerings is also prevalent in one form or another in Buddhist Tantra. This dynamic was central to the Kapalika sect whose influence upon the corpus of Yogini Tantas was considerable. While few scholars can agree who influenced who, the most important thing is that these traditions arose.

Light from the three seeds attracts wisdom nectar. Samaya and wisdom become inseparable and an ocean of nectar descends.

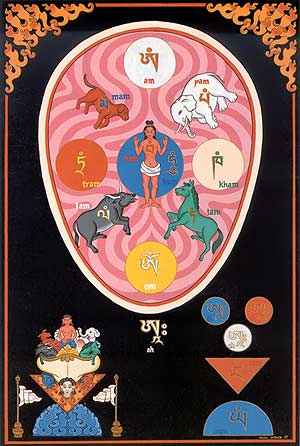

In Buddhist sadhanas the five meats and the five nectars share a certain equivalency to the Hindu Pancamakara. Rather than the transgressive five M’s (madya, mamsa, matsya, mudra and maithuna) we have the five meats: the flesh of cow, dog, horse, elephant and man, and the five nectars: semen, blood, flesh, urine, and feces. The five meats are representative of the five skandhas: form, feeling, discrimination, action, and consciousness. Likewise, the five elements: earth, water, fire, wind, correspond to the five nectars. Depending on the explanation lineage of the inner offering, these associations may vary, but generally the essence is the same. In this practice we join the five wisdoms with the five elements to produce a non-dual intoxicating ambrosia that has the capability of revealing the qualities of awakening and in that sense provides a powerful spring-board of potential realization. In other words we are joining our perceptions with the objects of our perceptions- entering into direct relationship with phenomena; uncontrived and expansive. We boil perceptions and the ability to perceive in a five dimensional way thereby naturally releasing our habitual confused samsaric reaction for a more aware equanimous relationship with the world around and within us. This is the very mechanism of samsara/nirvana! What’s more, as this mechanism unfolds, it reveals the don-dual vastness of Dharmakaya, a spring-board for sacred outlook. For a moment everything is okay, relaxed into ease.

These substances emanate from their specific syllables and are brought together to be mixed in a kapala (skull cap bowl), one then generates a flow of prana which strikes syllables for fire and wind underneath the kapala to make its contents boil and in a sense unify. This now ambrosial nectar (amrita) emits the syllables Om, Ah, Hung, dispersing the blessing of pure Buddha body, speech and mind. This simply radiates. It is used to bless torma offerings and nectar used in offerings, or in a more general way tsok offerings as well as the general environment.

Om Ah Hung Ha Ho Hri Hung Hung Phe Phe So Ha.

There is another side to this as well; it seems an importantly powerful thing to keep in mind at some level that the five meats and five nectars were intended to be transgressive repulsive substances. Shocking and caste destroying, they arose directly out of the charnel ground culture that figures so largely in Buddhist Tantra. There is power in our response to disgust, to fear, guilt, lust and all those emotions that lurk around the edges of our movement through the world; we all have our own relationships to purity and impurity, and they are a lot more complicated than we like to assume. Guilt, fear, self-righteousness, abandonment, woe, depression, anger, disgust- an army of emotions- are related to how and why we connect to/react to purity and impurity- we carry these reactions with us wherever we go as we label the things around us as clean and or unclean, desirable and undesirable.

A few years ago I was speaking with the abbot of a Buddhist monastery in India about the historical development of tantric applications of using impure substances. In his reply he said that things are so much more different today in trying to connect with these practices. It’s hard to see rotting corpses, scary wild animals feasting on human remains, lepers, one can’t go down to a charnel ground these days to do a puja around bodies in various states of decay. With the use of toilet paper, some of the stigma of the use of the left hand in India is less powerful, and in western countries there never really was the same kind of stigma in this regard. This he suggested that this is one of the reasons why we use/rely upon visualizations- they can be quite powerful.

However, I wonder where these places of fear are- we all have them- perhaps they are more individualized, or abstracted. Homelessness, illness, mental illness, terrorism, and death, perhaps these are some of the newer “untouchables” of our times. It is important to locate them for ourselves, touch the fear or terror that they bring, and then offer them up- the essence of fear and terror is mind, and mind’s essence is primordially pure. If we can take these sources of impurity and throw them in a pot and cook them with wind and fire, energy and exhaustive passion, they can be seen for what they are, not much different from the purity and wholesomeness that we so easily cling to. What then is the difference? And why to we always run from one towards the other?

New York Zen Center for Contemplative Care on TV!

This weekend a segment of the television show Religion and News Ethics Weekly will broadcast a taste of the New York Zen Center for Contemplative Care chaplaincy training program on PBS which you can also watch here. NYZCCC is a rich and rigorous CPE training program that is truly unique. I am constantly challenged by the depth of the curriculum as well as that of the instructors, Koshin Paley Ellison, Robert Chodo Campbell, and Trudi Jinpu Hirsch. Currently I am half way through my first of two units of CPE through NYZCCC’s year long extended unit program, was a participant in their Foundations in Contemplative Care program last year, and look forward to more training with them in the future. I can’t say enough wonderful things about the program and how wonderfully rare it is.

I invite you too to explore NYZCCC here…

Milarepa on the nature of mind

This is a particularly intimate and moving song of instruction by Milarepa for his student Gampopa. The imagery of a parent concerned for his child contributes to the sense of closeness between the teacher and student in this song, it also shows how subtle some of the maras (perceptual delusions) that we experience along the way can be. Milarepa as the tender father helps to point out some of the pitfalls that obscure the natural luminosity of the mind’s essential nature.

Following along with the parenting metaphor for a moment, I am reminded of a teacher who once reminded a friend and I that once one begins to meditate, no matter how much time spent in meditation, or its frequency, we should act as if we are pregnant; or we should know that we are pregnant with the innumerable qualities and benefits of Buddhahood. How long the gestation period will be is hard to know, but one day we will give birth to the clear and stainless realization of our mind. All it takes is to begin a meditation practice and examine what effects it has on our perception and our relative well-being; once we are pregnant with this potential awakening, we should guard ourselves against that which complicates and distracts our meditation practice. The tone that Milarepa sets in this song is gentle and supportive; how can we be this way with ourselves in our practice?

A Song of Instruction to Gampopa

By Milarepa

Son, when simplicity dawns in the mind,

Do not follow after conventional terms.

There’s a danger you’ll get trapped in the eight Dharma’s circle.

Rest in a state free of pride.

Do you understand this, Teacher from Central Tibet?

Do you understand this, Takpo Lhajey?

When self-liberation dawns from within,

Do not engage in the reasonings of logic.

There’s a danger you’ll just waste your energy.

Son, rest free of thoughts.

Do you understand this, Teacher from Central Tibet?

Do you understand this, Takpo Lhajey?

When you realize your own mind is emptiness,

Do not engage in the reasoning “beyond one or many”.

There is a danger that you’ll fall into a nihilistic emptiness.

Do you understand this, Teacher from Central Tibet?

Do you understand this, Takpo Lhajey?

When immersed in Mahamudra meditaion,

Do not exert yourself in virtuous acts of body and speech.

There’s a danger the wisdom of nonthought will disappear.

Son, rest uncontrived and loose.

Do you understand this, Teacher from Central Tibet?

Do you understand this, Takpo Lhajey?

When the signs foretold by the scriptures arise,

Do not boast with joy or cling to them.

There’s a danger you’ll get the prophecy of maras instead.

Rest free of clinging.

Do you understand this, Teacher from Central Tibet?

Do you understand this, Takpo Lhajey?

When you gain resolution regarding your mind,

Do not yearn for the higher cognitive powers.

There’s a danger you’ll be carried away by the mara of pretentiousness.

Son, rest free of fear and hope.

Do you understand this, Teacher from Central Tibet?

Do you understand this, Takpo Lhajey?[i]

[i] Songs and Instructions of the Karmapas. Nalandabodhi Publications. 2006. Pg. 25-26.

Pointing out the Self with the Iron Hook of Mind

In the first post for Ganachakra I wrote a partial introduction to the late Kyabje Pathing Rinpoche. I would like to return to Pathing Rinpoche, to share a teaching song he composed and shared with my dharma brother Erik Bloom and I.

If I had to be stranded on a deserted isle with one set of instructions, just one teaching, I would choose this one. The title alone sets the tone, it is strong and direct. Pathing Rinpoche is clear in his description of the view, the path (of cultivating the view), and the fruition (of familiarizing oneself with the view; how to blend it with your being). The tantric imagery is rich and beautiful. This is a truly precious a wonderful teaching. If you have a moment, take a second to clear your mind, settle down, and have a read. I’d love to hear what you feel after reading it.

Instructions on Pointing Out the Faults of Self with the Iron Hook of Mind

In general, everything in the universe, outer, inner and secret, I offer to satisfy and benefit the six classes of beings.

The whole field of accumulation, the three Jewels as well as the three kayas, the entire universe I offer to the inner and secret deities, may they be satisfied.

To the Male and female yogis and yoginis I offer vajra food and vajra water, may they be satisfied.

Primordial Awareness, the mandala of pure amrita, I offer so that those in the lower realms may be satisfied.

The body mandala deities who are the union of bliss and emptiness, who are primordial awareness, may they be satisfied.

Everyone, in an outer and inner sense, is a dakini; to them I offer this melodious song, may they be satisfied.

As a last resort to stop all filthy activities I offer this torma, may the six protectors and local deities be satisfied.

In this context sing this vajra song if you like.

Just as the many male and female deities, dress in the disguise of a heruka. When prostrating do so in accordance with our noble tradition.

First, make a humble request as follows:

Ho!

Please consider me. Three times.

The lord of empowerments, Samantabhadra’s great mandala of perfection is good and noble.

As stated in The Pearl Necklace, the ocean of the supreme assembly, both outer and inner, come and join together in an excellent manner to make the offering complete.

Visualize that the offering assembly enters and confer empowerment into the mandala. One should exert oneself in singing this song. Thus I ask you to pay attention to the reality of the inconceivable power of the ocean-like display of this vajra song.

Karma and aspiration, dependent origination and the like appears as it does.

In this way, make offerings to the assembly when renouncing that is which to be abandoned.

Wholly let go of finding amusement in creating conflict.

Revile material things and so on, reproach that which is rough and coarse.

Just like Guru Rinpoche, the Lord of Uddiyana, one should arise with the power akin to a wolf when coming to the ganachakra.

Endowed with the three authentic perceptions, the female goddesses of the ganachakra should be visualized as nectar. If you do not realize this you will be reborn as a preta.

In this regard, endowed with the three authentic perceptions, think of the Lama as Heruka and the Buddhas with their consorts.

Think of the Vajra siblings, fellow practioners, as male and female deities.

Recognize the blessings of the Ganachakra.

Do not be separated from the three circumstances.

May we never be separate from the yidam; our ordinary body.

May we never be separate the mantra of speech.

May we never be separate from realizing the nature of mind.

May we be free from the three doubts.

May we be free from any doubt regarding the tantric textswhich are the enlightened speech of the Lama.

May we be free from any doubt as to whether ganachakra is clean or unclean.

May we be free from any doubt concerning secret conduct.

The three things that are not to be done.

One should abandon carelessness of conduct.

One should not allow aversion (hatred, anger) and envy consume the mind.

Conceptual thought (discursiveness) is not appropriate.

It is improper for Bhikshus to take meat and beer with fear, or based upon discursiveness.

It is improper to continually engage in Brahmanic pure expression out of conceptual thought.

It is improper to engage in actions and conduct which is upon worries of good or bad.

These are the three unwholesome actions not to accumulate.

For one who follows the path introduced by the Lama, do not accumulate unwholesome actions.

The path of the spiritual instructions is profound, do not accumulate unwholesome actions.

Do not accumulate unwholesome towards vajra brothers and sisters or phenomena in general!

These are the three things not to give freely.

Do not give secret blessed substances to others.

Do not give away the oral instructions.

Do not perform offerings when not suitable.

These are the three secrets.

Secretly, one should make offerings when the feast assembly gathers.

Secretly, one should manifest great numbers of deities.

Secretly, perform activities and deeds that lead towards liberation, this is the essence.

These are the three things not to practice!

Do not call upon the Lama without respect and devotion.

Do not call upon the feast gathering in an “ordinary” way.

Do not apply unwholesome forces [actions and thoughts] towards vajra sisters and brothers.

Thus, in knowing what to adopt and what to abandon, the magnificent blessings of this ganachakra will flood rotten karma everywhere and siddhis will arise.

Recognize this!

Sing this feast song if you like; through it you will realize the essence of dependent origination, karma, and so on. May you receive inspiration from this vajra song.

In the sky of emptiness this sun dawns,

Appearing, but not remaining, it will proceed to cross over.

Similarly, according to books, precious human rebirth has happened in this lifetime, not an “ordinary” birth.

As soon as one is reborn, one does not remain, death arrives.

Over a long period of time one remains, not accounting for one’s actions.

One should approach the path with zeal and diligence while sowing the seeds of Dharma.

Keep Meditating!

In the marketplace people go this way and that, continually abiding in daily hustle and bustle.

At all times separate yourself from the company of others.

Create an example similar to past masters.

At all times do not remain separate from the master.

Right now, accompany the master.

Discuss the profound Dharma so that you may resolve for yourself its excellence.

Just as the honey bee gathers the sweet essence of flowers without regard for the honey gathered

by others, it is just so regarding material goods in the present lifetime.

Do not desire the accumulation of wealth gathered by others; attachments to the desire realm should not be great.

Whatever you have in terms of wealth, let it go!

Commonplace work and responsibilities, what?!

Due to sporadic effort one will miss the fruits of the autumn harvest.

Similarly, through sporadic effort and enthusiasm towards the practice of meditation over the length of a whole lifetime, one will not experience awakening.

Do not engage in practice which is either too tight or too loose.

Constantly, day and night, generate enthusiastic diligence, keep meditating!

Achieve the freedoms and advantages that this human birth can bring here and now!

In this and in later lives, accomplish the aspiration towards liberation.

In your free time guard that the frame of one’s mind does not let it become thin and weak.

Harmonize your mind with its experiences through the practice of meditation so that they dissolve together.

Through this ganachakra of liberated conditions, may we receive the esoteric revelation of this song of spiritual experience now in this very lifetime.

Here, at this ganachakra pervading the entire sky, may all sentient beings conquer the undying Dharmakaya citadel.

Gewo!

Written by the authentic Phul Chung Tulku, Known as Pathing Rinpoche, incarnation of the Mahasiddha Kukkuripa.

Translated by his student Karma Tenzin Changchub Thinley (Repa Dorje Odzer) in the western pure land of Brooklyn, with the gracious guidance from the venerable Khenpo Lodro Donyo. All errors are mine. Sarva Mangalam!

![Validate my RSS feed [Valid RSS]](valid-rss-rogers.png)